Thought this was also an easy to understand explanation besides the ones given above:

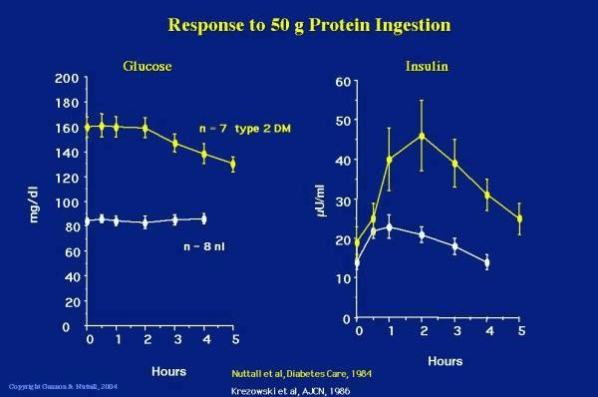

Insulin response to protein for people with diabetes:

Things are different if you have diabetes.

Insulin resistance means that between our fatty liver and insulin resistant adipose tissue, things don’t work as smoothly.

While your blood sugar may rise or fall in response to protein, needs to rise a lot more while you metabolise the protein to build muscle and repair your organs.

Unfortunately, people who are insulin resistant may struggle to build muscle effectively due to insulin resistance. Then the higher levels of insulin may drive them to store more fat in the process.[12] Becoming insulin sensitive is important!

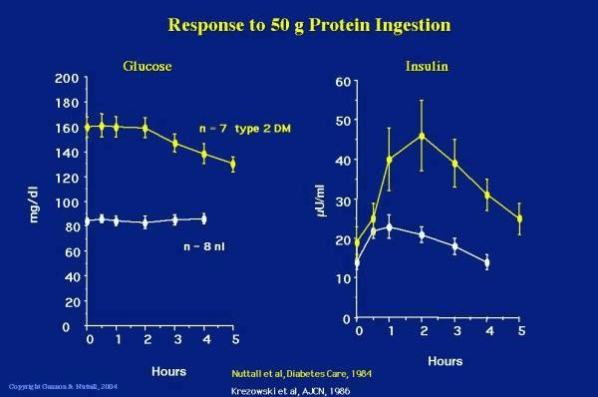

The chart below shows the difference in the blood glucose and insulin response to protein in a group of people who are metabolically healthy (white lines) versus people who have type 2 diabetes (yellow lines).[13]

People with diabetes may see their glucose levels drop from a high level after a large protein meal and will have a much greater insulin response due to their insulin resistance. People with more advanced diabetes (i.e. beta cell burn out or Type 1 diabetes) may even see their blood sugar rise. Their ability to produce insulin to metabolise the protein and keep glycogen in storage cannot keep up with the demand.

Drawing on the brake/accelerator analogy, it’s not necessarily protein turning into glucose in the blood stream via gluconeogenesis, but rather the glucagon kicking in and a sluggish insulin response that isn’t able to balance out the glucagon response to keep the glycogen locked away in the liver.

Healthy people will be able to balance the opposing hormonal forces of the insulin (brake) and the glucagon (accelerator), but if we are insulin resistant and/or don’t have a properly functioning pancreas (brake), we won’t be able to produce as much insulin to balance the glucagon response.

Someone who is insulin resistant has normally functioning accelerator pedal (glucagon stimulating glucose release in the blood) but a faulty brake (insulin).

More insulin or less protein?

So, what is the problem here?

Why are Monica’s blood sugars rising?

Is it too much protein?

Or not enough insulin?

I think the best way to explain the rise in blood sugars is that there is not enough insulin to keep the glycogen locked away in her liver and metabolise the protein to build muscle and repair her organs at the same time.

Meanwhile, the glycogen pedal is pushed down as it normally would be in response to a protein which is driving the glucose up in her bloodstream.

There is just not enough insulin in the gas tank (pancreas) to do everything that needs to be done.

So, if Monica had a choice, should she:

- A. Keep her blood sugars stable and stop metabolising protein to repair her muscles and organs,

- B. Metabolise protein to build her muscles and repair her organs while letting her blood sugars drift up, or

- C. Both of the above.

Personally, I think the correct answer is C.

While it’s probably not wise to go hog-wild with protein supplements and powders if you have diabetes, swinging to the other extreme to target minimal protein levels is a sure way to end up with a poor nutritional outcome.

According to Simpson and Raubenheimer in Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis (2005), people with diabetes may actually need to eat more protein to ensure that they have adequate amounts to build lean muscle mass given that higher levels of gluconeogenesis may cause more protein loss to glucose due to their insulin resistance.

”… One source of protein loss is hepatic gluconeogenesis, whereby amino acids are used to produce glucose. This is inhibited by insulin, as is the breakdown of muscle proteins to release amino acids, and therefore occurs mainly during periods of fasting (or low carb).

However, inhibition of gluconeogenesis and protein catabolism is impaired when insulin release is abnormal, insulin resistance occurs, or when circulating levels of free fatty acids in the blood are high. These are interdependent conditions that are associated with overweight and obesity, and are especially pronounced in type 2 diabetes (12,34).

It might be predicted that the result of higher rates of hepatic gluconeogenesis will be an INCREASED requirement for protein in the diet. …” …More

Related:

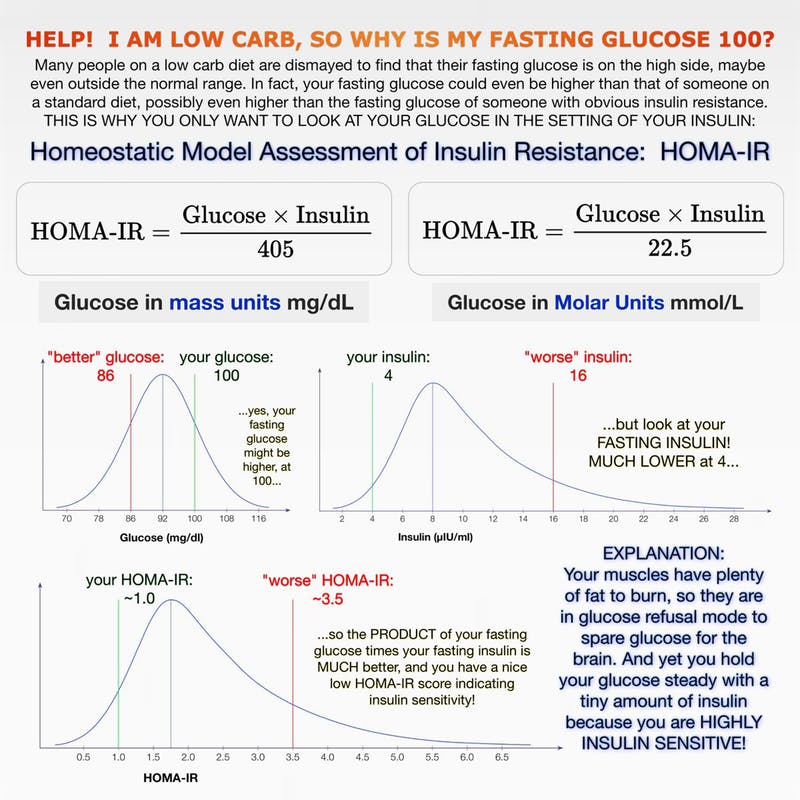

[1] HOMA-IR score your becoming “highly insulin sensitive”