You could be right, but I though gluconeogenesis was supposed to be a fairly tightly-regulated process. In any case, protein is not generally metabolised, but rather is cleaved into its constituent amino acids, which are then re-combined into new proteins. The body’s limited ability to store amino acids generally means that the excess from the labile pool gets excreted in the urine, or so I understand. Somebody please correct me if I’ve got it wrong.

Does a healthy ketogenic diet cause irreversible insulin resistance?

Slightly tangential to the topic, but only slightly …

I find, as others have reported, that when I enjoy a glass of dry red wine an hour or so before dinner (that’s wine, not vinegar), my blood glucose also drops by roughly 10 points (mg/dL) within about 30 minutes.

@SunnyNC Given your concern about the absolute level of glycolated RBC (which I respect even if I don’t personally worry re: the same concern), if you’re determined to get your HbA1c down one way or another, consider enjoying a glass of red wine as the sun sets? Might even help lower stress/cortisol too

FWIW, these days my BG meanders between mid-90s and mid 110-teens, and (1.5 hrs post-prandial) can even reach as high as 120 mg/dL. My sense is that highly restricted-arb eating + 2MAD + regular exercise are allowing my red blood cells to enjoy longer lives … so they have a chance to get more glycolated. If so, my wishful thought: HbA1c is a slippery metric for us healthy keto-eaters

Anyhow, while my pre- vs post-meal glucose swings seem fairly minimal in the scheme of things, based on old lab reports I believe my fasting glucose level is about 10 mg/dL higher than it had been in my pre-keto days.

I’ve noted elsewhere more than once that both ethanol and vinegar produce the same metabolic results: suppression of gluconeogenesis, enhancement of ketogenesis and clearing glucose from the blood. Up front ethanol generates aldehyde which is not a good thing but manageable in small amounts from time to time.

The crux for me is whether or not either is a viable tool to accomplish those things and whether or not it’s desirable to try to do so.

Yes, that’s true protein does get cleaved into amino acids, but the body can utilize those amino acids to make glucose via gluconeogenesis pathway. I don’t know of any studies and this is just conjecture, but perhaps long time ketogenic dieters become more efficient with protein and more glucose in created.

Musing again on this thread’s heading ("Does a healthy ketogenic diet cause irreversible insulin resistance?") prompts me to note that virtually all of the YouTube offerings on physiological insulin resistance (PIR) - observed as a keto-induced modest rise in fasting blood glucose - seem to agree on one central point… [Apologies if this was already addressed in the previous 200 entries to this thread]

If you want to “pass” an OGTT while on keto, eat some specified amount of starchy carbs for a few days beforehand. Then (we’re told) you will reactivate the glucose receptors in muscle tissue to their pre-keto insulin sensitivity and you shall obtain a more meaningful (acceptable?) result on your OGTT.

Putting aside confusion over the distinction between science and YouTube, if such guidance is correct, it suggests that whatever PIR results from longer-term keto, apparently it’s reversible in a matter of 2-3 days.

That’s in stark contrast to how long it takes for fat adaption to occur in LFHC/SAD eaters. Then again, most LFHC eaters going keto were eating SAD for their entire adult lives. By contrast, keto-eaters were likely doing so for a much shorter stretch of time. Perhaps that’s why restoration of insulin sensitivity in the muscular takes just a few days (compared to fat adaptation)?

None of which directly addresses @SunnyNC’s question seen elsewhere: Why would higher serum glucose in a carb-restricted eater be less harmful than the same glucose levels in a high-carb eater? Glucose is as glucose does, right?

[Personal note: As a guy whose FBG now hovers around 100 mg/dL and swings +/- pre/post-prandial by a modest 10-15 mg/dl, I’m not experiencing firsthand health angst, but of course the whole topic continues to intrigue me. All reliable science welcomed!]

There are two main categories of amino acid, one of which is more easily converted into fatty acids, the other which is more easily converted into glucose, and I believe a few amino acids can be converted into both. While it used to be believed that every excess amino acid got converted into glucose, it is now believed that gluconeogenesis is more tightly regulated than that.

Actually, I believe it is the other way round, and that the idea of eating some carbohydrate is to avoid looking too insulin-sensitive, not insulin-resistant. My understanding (which well may be wrong) is that glucose receptors are never down-regulated, even when we are fat-adapted. It is the damage to mitochondria from excessive glucose consumption, and the down-regulation of certain cellular processes required for fatty-acid metabolism that need to be reversed when we go keto, in the process we call “fat-adaptation” or “keto-adaptation.” I have never heard of anyone’s needing to readapt to glucose metabolism after stopping a ketogenic diet.

Remember that the other name for “physiological insulin resistance” is “adaptative glucose-sparing.” The logic behind the concept, regardless of how we choose to name it, is that skeletal muscles, once fat adapted, prefer to metabolise fatty acids and pass up ketones and glucose, sparing them for other organs and cells that need them. Yet when there is a need for explosive power, fat-adapted skeletal muscles can still immediately make use of the glucose that the liver sends them in the form of glycogen.

To me, it makes no sense that a muscle cell would lose the ability to metabolise glucose, because explosive power is often needed when running down a mammoth or in fighting a sabre-toothed tiger. Also, given how important it is to avoid hyperglycaemia and how skeletal muscle and adipose tissue are the two main glucose sinks, it would not make evolutionary sense for a cell to lose the ability to metabolise glucose. Fatty acid metabolism is not as crucial an ability.

@PaulL It may well be the other way round… but that’s clearly not what these folks I’m referring to are saying.

I’ve provided an indicative sampling below; there are plenty of others saying these same things. Long term keto makes you insulin-resistant - not insulin-sensitive. The “R” in “PIR” stands for “resistance.”

And so, taking an OGTT without re-priming your muscle receptors for glucose first, the results will cause you to appear highly insulin-resistant (presumably because you are) … and the presumption will be that your insulin resistance is the sign of pathology.

Taking an OGTT without prepping your muscular will invite confusion as to the distinction between pathological vs physiological insulin resistance.

Both pathologic and physiologic start with “P” … but the “R” is still for resistance

Disclaimer: I’m not a fan of getting my science from YouTube and haven’t delved personally into the underlying research to which these folks are referring. But the idea of prepping for an OGTT by carb-loading for several days in advance is to turn muscle glucose receptors back on again because the tissues have become insulin resistant.

My larger point was that these folks claim that reversing insulin resistance is fast and easy - i.e., not a long-term/permanent state. The thread heading was about “irreversible” IR, so that was the point of offering these points about the OGTT on keto.

Have a look and let me know if I’ve wandered off base.

-

Mark O’Neil’s article, the first one you link, has some very good references at the end. He gets a lot of credit for making quite a bit of use of articles by Petro Dobromilskiyj (Peter of the Hyperlipid blog), whom I personally consider to be very reliable Peter may be a veterinary anaesthesiologist, but he has a great deal of experience interpreting research papers, and he is possessed of an amazingly sharp mind.

-

Thomas Delauer, the second link, is a populariser, not a researcher. I don’t know his educational background, but I do know he does not always get the details correct when he passes on information that he has read. His videos generally have no citations of the sources for his claims, which I find troubling. He also has products to sell, which can be a problem.

-

Personally, I take everything Ted Naiman (#3) says with a large salt crystal. He is known for taking an idea and running with it, well past what the data can support. His ideas are interesting, and I try not to dismiss any of them out of hand, but I always treat them with great caution. Though a doctor, he is not himself a researcher, and his enthusiasm for an intriguing idea can run away with him. He is skimpy with the citations, though a bit better than Mr. Delaurer.

Here’s something that was first mentioned in passing above here. Specifically, the role of insulin in all this so-called resistance.

2. Insulin is low — an important difference

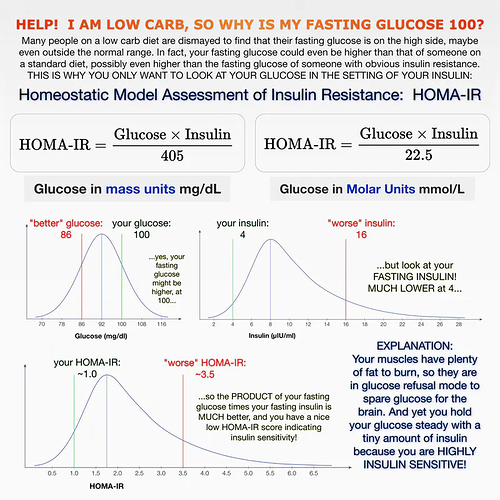

Only testing fasting blood glucose without testing fasting insulin tells you very little. That’s because two people could have exactly that same fasting blood glucose levels and have very different circulating insulin levels.

It is all about the relationship between glucose and insulin and how they work in concert. This is called the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance or HOMA-IR. The name is a mouthful, but it simply means that the body is always trying to keep its essential systems in balance or in an equilibrium — called homeostasis. Insulin is working against glucose in an attempt to keep blood sugar levels stable, a.k.a in homeostasis.

In one individual — for example someone with pre-diabetes, type 2 diabetes, or PCOS — insulin may over time be pulsed out in higher and higher amounts just to keep the blood sugar relatively stable. While fasting blood glucose could still be in the normal range, it is taking increasing amounts of insulin to keep it there. As insulin resistance develops, and insulin becomes increasingly ineffective to bring blood sugars down, blood sugars will eventually rise too high.

In a second individual — someone who has been on the keto diet for a number of months and is now burning fat for energy — much lower amounts of insulin are being pulsed by the pancreas to keep the glucose stable. You have now, therefore, improved your insulin resistance and only need small amounts of insulin to keep glucose in check.

Dr. Naiman’s graph shows, if you know your fasting blood glucose and your fasting insulin, the HOMA-IR equation can tell you how insulin sensitive or insulin resistant you are. If your fasting blood sugar is 5.7 mmol/L (103 mg/dL) and your insulin is high, too, over 12 μU/mL, you are insulin resistant and may be on your way to type 2 diabetes. If your blood sugar is 5.7 mmol/L but your fasting insulin is under 9 μU/mL, you are insulin sensitive and may be in “glucose refusal” mode from a low-carb diet.

Most doctors do not yet check for fasting insulin with a fasting blood glucose test. You usually have to ask for it.

My takeaway is that looking at glucose in isolation tells you not much. Yes, of course, if you’re diabetic or prediabetic it tells you something. But if you’re normal and have been doing keto long term and FBG seems to be rising - get an insulin test before getting too excited about it. If in fact you have high FBG and high insulin - that’s a problem.

Also, I think the terms ‘adaptive glucose sparing’ and ‘physiological insulin resistance’ are both misleading terms. Both, especially PIR, suggest something undesirable is going on when in fact it may not and probably is not. In the link I’ve posted immediately above Amy Berger discusses some of the functions of gluconeogenesis that are likely relevant to this issue, like how much and how fast glucose gets generated and where it goes.

@PaulL and @amwassil Thank you both for your replies.

Again, I’m not vouching for these videos and blog posts. I have not yet delved into the relevant research (although I’ll now devote some time to doing so).

My point is simply this: these are keto advocates who speak of long-term keto leading to an increase in insulin-resistance and they claim that one can easily reverse this outcome by reintroducing carbs within a fairly short timeframe.

If they are correct it makes “physiological” IR anything but irreversible (i.e., 2-3 days to reverse).

FWIW, I share no concern regarding my own (slightly) elevated FBG since going keto. I’d rather be “fat-adapted” than “carb-adapted” - any day.

My point was to give @PaulL a chance to reconsider his earlier post and give others a chance to exhale and relax a bit about what’s being discussed as keto-induced insulin resistance.

Thanks Michael for bringing insulin back into the discussion. Every time I read this thread I think of Ben Bikman postulating that the slower disposal of glucose might be due to the loss of the first phase insulin response. In a high carb eater, the beta cells of the pancreas store a bolus of insulin ready to dump quickly into the blood stream when carbohydrate is ingested. In a ketogenic eater, the beta cells make insulin as required, which is slower yet adequate to keep a ketogenic metabolism safe from large blood glucose swings.

Bikman says that the body is always aiming for efficiency, so it makes sense that the pancreas beta cells don’t keep a large store of insulin ready for an event that never happens. Yet over a few days this insulin production and storage can ramp up. This is his theory on “physiological insulin resistance” - a term he doesn’t find useful either.

I got this from a Bikman podcast interview and he also mentioned that this isn’t a proven explanation for this PIR, just his suspicion.

My personal analogy is my suntan; my skin changes the amount of melanin in the cells according to whether it needs to protect against sun burning, or make more vitamin D. The change takes many days then stays for a while. A seasonal change, possibly analogous to summer fruits giving way to winter meat eating.

There may be glucose metabolism pathways involved as well. One suggested answer doesn’t exclude the complexity of other effects

Thanks for mentioning Ben Bikman!

Note: for those, like me, who prefer to read there’s a ‘highlight’ transcript following the audio.

Thank you for trying to help. I’ve read. It is just guessing, no evidence high BG isn’t bad if one is in ketosis.

I see it as 2 separate things:

-

high insulin is bad. I’m happy I’m keeping mine as low as possible with keto.

-

high BG is bad. I’m tweaking keto and exercise to keep it lower than it is. Where is the “high BG” threshold? They don’t know. That link is just a blog. Even there they say “may be”.

The problem is (or it isn’t, but I’ve found no evidence to reassure me that it is ik): on a normal person glucagon says: liver, do your job and dump glucose! Liver obliges!

That’s wonderful. However, 2 problems: if ketones are so wonderful and I’m in ketosis, why I need so much glucose to get up a flight of stairs?

Second problem: on a normal person, by at least 2 processes, the muscles that needed the glucose use it and your blood level is lower again in no time.

In a few of us posting in this and other threads, it stays up.

Suppose it stays up because my muscles actually prefer ketones. Fine by me to flee the tiger running. However, that glucose that my liver dumped is therefore being kept unattended in my plasma.

I haven’t found evidence it isn’t doing what too much glucose in your blood does: damage!

Besides your wishful thinking (mine too, I want to hope!), do you know for sure from what level high BG is ok? For a woman?

I added “for a woman”, because mean BG increases with age. For women it seems to be linear. By that curve, instead of in my 50s, I’m in my 70s!

“He feels”, “perhaps”…

If I had t2 patients who finally got to control their BG and get it pretty level, I wouldn’t worry as much as I was worrying before.

How much you worry also depends where you start, what are your conditions. Also, if a person is getting depression from trying so hard to control BG, or other things, as a dr I would also try to find a place where there’s a balance, a realistic place where to tell my patients that it is ok. Quality of life passes also by being able to balance these things. So, I totally see where he may be coming from.

I appreciate you trying to help. Thank you very much!

The interesting point for me is that there isn’t any evidence high BG is bad, either, if one is in ketosis. We need a lot more research before we start jumping to conclusions.

A lot of the damage of the standard American diet comes from the elevated insulin that results from the elevated glucose. So I’m wondering just how damaging elevated glucose might be, if our insulin is still low enough for us to remain in ketosis.

Glucagon and insulin are not the only things regulating gluconeogenesis. A study on mice of (various types) that lack the ability to produce neither glucagon nor insulin (they start with mice that genetically lack the ability to make one of them, and then knock out their ability to make the other) shows that they never become diabetic, and their blood sugar remains stable.

Apparently, Type I diabetes is a disease of being able to produce glucagon without being able to produce insulin to regulate it (each of them helps regulate how much of the other the pancreas produces, since the α- and β- cells are right next to each other in the Islets of Langerhans). With both hormones out of the picture, other bodily mechanisms take over to regulate blood sugar.

For one thing, being in ketosis means that fatty acid metabolism is powering our endurance performance. But we still need glucose to power our explosive performance.

I should add that these remarks of mine are pretty speculative. But if people can argue that there is no evidence to show that long-term keto eating is safe (despite the experiences of quite a few people and the evolutionary evidence), then it can also be argued that there is no evidence to show that long-term keto eating is unsafe, either. What we need is to gather data. As the Dudes’ dogma goes: “Show us the data!”