I never got my HbA1c tested until I was low carb/keto for a while. About 6 months into low carb, it was 5.4. It went to 5.6 then down all the way to 4.9, and now is 5.1 the last few times. On 1/1/20, I will be low carb/keto 6 years.

The problem I see with HbA1c, for those who have been keto for a while, is that my blood sugar goes up if I exercise or if I do physical work around the house or both. For instance, here’s this morning’s workout (only body weight lifting):

First column after time is Keto Mojo (home); then Keto Mojo (work); then ketonix; then blood sugar; then notes.

An about 10 point rise in blood sugar isn’t unusual. But this is not the “bad” glycation being caused by excessive sugar intake.

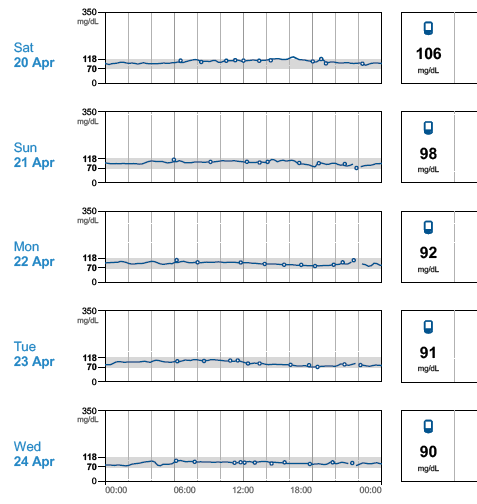

Consider the following too. These are from my FreeStyle Libre CGM. Saturday, I went jogging, then worked on the house all day. Sunday, we went to church, came back, and I worked on the house all day. Tuesday morning, I went to the gym. Monday and Wednesday were no workout days and were primarily sitting at work. Note that every day that involves exercise causes higher glucose for some or all of the day (see particularly Saturday and Sunday):

If I exercise and do work on my house involving physical activity, my average blood sugar is 106 (Saturday); instead, if I sit in my office and do no exercise at all, my average blood sugar is 90 (Wednesday).

Yet, which is healthier overall? I’d argue Saturday, but this will cause a higher HbA1c reading.

Thus, HbA1c, for those of us who are keto and doing any type of “exercise” including working around the house, is not a great marker of health.

Your thoughts?