Originally published at: https://ketowomanpodcast.com/maggie-tookey-transcript/

This transcript is brought to you thanks to the hard work of Liz Myers.

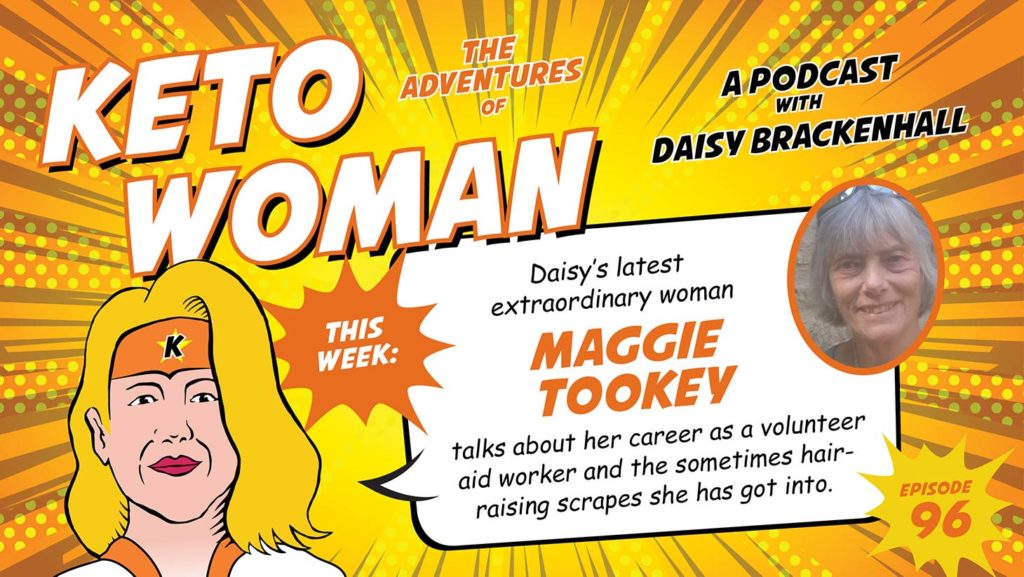

Welcome Maggie, to the Keto Woman podcast. How are you doing today?

Fine, thank you.

Now, we've known each other for a long time, and I have to say that when I started this podcast, I had you in mind to interview -- because I think people will find your story and what you do really interesting. So, going away a little bit from the kind of people I usually interview in that you're not keto, but you're certainly extraordinary. It's nice to be here, and be here with you, actually face to face in my living room, today, here in sunny France. So perhaps you could just tell the listeners a bit about you?

Oh, where to begin really? The job I've had for the last 18, 19 years was a total change of direction for me, because before that I'd been a teacher in a secondary modern school in North Yorkshire for 20 some years I suppose. Something like that. And I decided, although I loved the job - and I really did love the job teaching, it was great, lots of challenges - but I decided it was time to go. One year I was cycling through Europe on a summer holiday, and I just decided I wasn't going to go back to teaching that September, and I'd already got my notice written out and I submitted it from Slovenia - actually Ljubljana - that was taken in by the office staff and I never went back, which was probably not such a nice way to leave. But that was just the way it was. So I decided that's what I'd do.

For a couple of years I was doing some supply teaching, and I was doing a few other bits and pieces, traveling, doing a lot of cycling, a lot of traveling across Europe, and had been to South America before that.

And the Kosovo war happened, 1999 roughly. It broke out, I think it was 1999, and out of the blue I got a phone call from an organization based in Canterbury to ask -- I don't know how they got my name. I have no idea, I never ever found out. But they asked me if I'd be prepared to drive a convoy vehicle to Kosovo with aid, because the war was, as everybody knows, it was a long time ago -- It was very vicious in Kosovo. The Serbs and the Albanian Muslims were being attacked. The Serbs were actually doing a lot of the attacking, both sides were entrenched in warfare, and the people were suffering very badly.

Villages were being burned, and some terrible things as happened also in the Bosnian war before that, although I wasn't involved with aid work in that particular confrontation. So I decided, okay, I would, I didn't know quite what to expect. I didn't know whether it would be or not dangerous. I just thought, why not? And I drove a vehicle out with a convoy to Kosovo. It was a very difficult time. The war was still just going on, although they were desperately trying to get some peace agreements going. Then of course the UK government decided to bomb Belgrade, which more or less ended the war. But where I was positioned up in the north in Mitrovica, there was still a lot of shelling going on. It was an interesting time, not having been in an area where they were shelling ever before, and rifles firing at night over the river into our areas.

We delivered the convoy, we delivered the stuff to the people who needed it, and people who lost everything, and then drove back to the UK. But I met somebody there who said, “Look, can you come back out? Because we have an organization working here in Mitrovica, which desperately needs volunteer help”. That was in the November of '99, and in the January/ February of 2000, I went out again with a van that somebody had lent me, full of stuff, and drove up north to Mitrovica by myself, which was a bit tricky. I stayed in Mitrovica, and I met this organization up there who were reconstructing Albanian villages from the shelling and the burning, and was trying to give people back some shelter. Big job, very big job funded by the EU, and I joined them and then I was there for three months, and that was the start of my aid working life really -- as a volunteer. I've always been a volunteer.

Was it interesting? I can't -- knowing you, I can see why somebody would contact you in the first place, but how fascinating that -- wow. I wonder where your name came from.

I don't know where it came from. I think I'd been writing some…I can't remember what it was. Definitely through some contact I had that I'd met doing something in that two-year period. Somebody had contacted this organization in Canterbury because they were involved with it and said, look, I bet I know somebody who will come out and you know, your shorter drives - I bet I know somebody will do it called Maggie. And I guess that's how it happened. But that's all I can imagine happened. So that was it - three months in the north of Kosovo as the war sort of died down and reconstructing and trying to help people and build houses and deliver shelter in the high mountain villages. So, that was the start of it.

I carried on working there over the next couple of years. And then in 2003 the organization called Edinburgh Direct Aid, which is the one I now work for, they asked me whether I'd be prepared to front a project working in the West Bank. The situation in the West Bank was getting ever more difficult. The occupation by Israel -- villages were being cut off from other villages. They started to build the new Israeli wall, and we were taking medical supplies to clinics that couldn't access the main towns. So, I went out to liaise with the Israeli army, which was another very challenging job and prepare for that. And then the rest of the team came out. Again, another very challenging, very sad, very distressing, very anger inducing job. Because I went out thinking, well the Israelis, you know, they suffered a lot of suicide bombs.

This is during the period when the Palestinians and Hamas and everybody was, you know, there were suicide bombers going, quite frequently bombs going off in buses in Israel. And of course, that was appalling. But on the other hand, the West Bank Palestinians were being denied access to Jerusalem, to Bethlehem, to lots of places. And so I felt sorry for both sides - but for my first 24 hours in the West Bank trying to get in into the West Bank through the main checkpoint at Ramallah, and I saw how people were treated and I'm afraid, I realized where my loyalties began to lie from there because what I saw go on was very distressing for people.

It's very difficult isn't it? Because it’s the everyday normal people who are affected by it.

Yes, exactly.

Not the same people or people who are in power controlling it. Different groups of people isn't it? That's where it gets very difficult I think, working out sort of where your sympathies lie because it's very emotive, isn't it when you are dealing with ordinary people?

So, I mean you have ordinary Israelis being killed, of course, on buses. And I mean at that time, if we were driving, if I was driving in Jerusalem, I was always told to not drive behind a bus because the risk was very high at that time. Sometimes you couldn't avoid it, but...

And how terrifying for people to live that that?

Yeah, absolutely. Very terrifying. But then you began to see what was going on, and why the Palestinians were reacting like that - it was out of just desperation. Then I got involved in... well, I pretended to be a journalist, but I was attending a lot of the peaceful rallies to try and stop the olive groves being destroyed for the wall. To stop the wall, preventing access to the farmer's fields. You know, farmers, Palestinian farmers who'd been working their fields and their olive groves for hundreds and hundreds of years, and old farmers who would sit -- I saw them sit down in the field and cry as bulldozers moved in.

Just sliced through them.

Army bulldozers just moving in and it's very difficult to stay impartial when you see the suffering of people. I didn't see any bus bombing, so I didn't see the aftermath of a bus bombing, which of course would be horrendous.

And of course, that's not the impact of the ordinary people in Palestine, is it?

No, it's not.

And that's not the farmer sitting down in his olive field doing that?

No, because if they been able to access their land as they'd always been able to and carry on with their - not to have these new settlements, which of course were settling into the West Bank, which was meant to be the land for the Palestinians. It's a very complicated situation. But settlements were growing up everywhere. Israeli settlements, they were a group of very right-wing Israelis that would go up to some hill top on the West Bank and they'd start to build simple wooden shelters and they say “This is Israeli land now”. And the army would protect it. So, then they'd have a big fence around it and a big wall and that would cut off another road.

The Palestinians couldn't drive on road certain roads to get to places. Gradually you saw all their freedom being eroded. Not only that, the checkpoints, the checkpoints became something like out of, oh I don't know, out of the Second World War - big wire fences, loads of barbed wire - big watch towers and turnstile gates that you had to queue for hours to get through. I mean, I've seen elderly people faint at those checkpoints because they just were having to wait so long to just to get home, having been to try and visit somebody in hospital and so - so many freedoms going. So that was the project we were doing, and we were trying to provide medical stuff to these small outlying clinics that were cut off from even towns like Ramallah and Bethlehem and Jerusalem. So that was quite an interesting time but, upsetting. Very upsetting, I found that.

Yeah, it must take its toll on you personally.

Yes, it does. I mean the women were incredible. The women would go peacefully to the army lines, because the army would have their Land Rovers lined up ready to move in with the bulldozers behind them. And the women would go… because the trouble with the men going, you've got these young men who pick up and throw stones, and you can understand why they want to throw stones at the army Land Rover. A, it was pointless, and B of course, the army would just fire rubber bullets and lots of tear gas. I mean the number of times I got caught up in tear gas was, oh...and once you've had a bad tear gas attack, you never ever forget it. Horrible.

But the women would go, and the army were much more restrained. The women would go, and they would talk to the men, talk to the army. There were some members of the Israeli army who were very reasonable, they looked a bit sad that they were having to do what they were doing. They were following orders, and the women, sometimes women would turn them back. They were more successful in turning the bulldozers back. And I would join those protests with the women. But of course, as a Westerner, I still had to pretend I was a journalist. Otherwise, I would have been not allowed back into Israel. You can't just, you know - that's what's happened to so many western protesters out there. They've not been allowed back in, and then you can't do anything.

So, there was that. Yes, that long distressing period of work there and then lots, and lots, and lots of work over the next 10 years. Pakistan earthquake, tsunami in Sri Lanka.

You go wherever you are needed?

Yeah. Where we are asked to go. I mean we're only so small, so we get very little funding so we can't do a great deal except that when there's a major disaster. The Pakistan earthquake in 2005 was the case in point. There is a huge Pakistan community in Edinburgh and in Glasgow where we are based, and when that earthquake struck - I mean killing 75,000 at a stroke, really more or less - our office was inundated with requests from wealthy Pakistani families saying, "Please can you go? We don't know what's happened to the family here. We don't know what's happening here. Please can you go, here's money. We can put in as much money as you need." And we got thousands and thousands of pounds in. So, I was sent out to see where the greatest need was and what we could best do with this money. I worked there from 2005 and of course it was terrible, the earthquake. I remember going into a mountain town called Balakot, and the stench of dead bodies - I'd never smelled anything like that. And the destruction, it would look like a nuclear bomb hit the place. And there were many towns like that. Living conditions were terrible. I was in a tent most of the time, and we were working up in the mountain villages where whole schools and whole villages had been wiped out. They had no shelter, they were sleeping out under winter, Pakistan winter.

It was very urgent. I went out and was transported from village to village by UN helicopter. I was dropped in with my tent and my gear and maybe another colleague and we would stay there for maybe a month working, and then the UN would supply us with what was needed, like stoves, winter stoves or whatever, and that went on. The projects developed. We put clinics in, we put so many things into the villages that had lost everything. They'd lost all their medical clinics.

That's why I like having heard your stories over the years, you get called into that emergency relief situation.

It is emergency relief. Yeah.

But then you also work on some projects that are going to have a more long term, sustainable impact.

Yeah. What we never do at Edinburgh Direct Aid, we never just go in, try to deal with an emergency when we can't deal with it - when we're not big enough to deal with an emergency.

But we do emergency aid in the places where big agencies don't get to. And they don't get often to the sort of, the really little difficult places high up or wherever and that's where we go. But then we tend to stay there and we tend to develop projects from that, like "Where most needs a medical clinic?" Because all the villages need...they're very highly populated and they all need medical care. We would start thinking what we used to do though, one of the best things we did, we'd send in a big container of aid, a 40 foot, 10 ton, 12 ton container. We'd empty it, distribute the stuff, and then most people just send the containers back to the pool. But I suggested that maybe we could buy the container and we could convert it into a clinic because it's a big space inside a container.

But the problem was getting that as a converted clinic, we could convert it - which we did, I did it with a fireman, a local fireman who came from Edinburgh and the two of us were out there two months converting this container - then we had to get it flown in to a mountain village at 10,000 feet. I went to the UN said, “Look, do you fancy this challenge? Because we've got it here and we can put it somewhere lower, but I know that this particular village, Koncan really needs it. I've been up there for several months in the tent and it's desperate”. So they talked about it. The pilots of the helicopters, great big helicopters they were using, they said, ”Okay, yeah, we'll do it” - the UN said we'll do it, why not?

We converted it on the field up in the northern part of Pakistan, unbeknownst to us, only about 300 meters from where Osama bin Laden was living and was later killed by the Americans. But we didn't know he was there, he was in a house next to the airfield. We converted it and then the day came when the UN were going to airlift it. It was a fine day, I was up in the mountains ready to receive it. Somebody else was down and waiting for the helicopter to attach the strops and carry it up over the mountains. Well, it's a story in itself really. I don't know whether you want me to tell you very briefly the story? They got it on the strops. They flew it on a pretty windy day up into the mountain at 10,000 feet. All the villagers were waiting to see it, about a thousand villagers, which we'd kept back up the hill. I was down with a special handpicked team of local villagers. We'd prepared the base, in came the helicopter. This thing was swaying and spinning in the air and the helicopter you could see was struggling bit to control anything.

And we were waiting for it and our job was to grab the strops as they came down to try and stabilize it. So we did, we ran onto this narrow terrace and grabbed the strops, brought it down - but the helicopter was spinning and you couldn't control it. We had to drop it, and we had to release the strops to release the helicopter before it crashed, climbing up onto the top of the thing and crawling on our stomachs to release those strops off the top of the roof of the container. Unfortunately it dropped it with the door jammed against the side of the mountain. After the two months of converting it, we couldn't even get in it and it was absolutely - well, I was at my lowest ebb at that point and sat down and had my head in my hands.

I just thought all that work, all that money - not that it costs so much. Suddenly I looked up the hillside and a thousand villagers were rushing down the hillside, like Zulu, and said, "Don't worry Maggie, you relax, you stay there, we'll move it". And of course, over the next five hours they got levers, they got planks of wood and millimeter by millimeter they moved it back onto its base until we could open all the doors and everything was absolutely fine. That was a tremendous memory I have of just how badly the villagers wanted their clinic, and how much they were prepared to do and how hard they were prepared to work. And when I was at the point of giving up, really.

I think it's also a good illustration of the relationships you develop, because as you mentioned before, you go into these places.

Yeah.

But then you stay a while and you develop these relationships and it has become, you know, a challenge that you want to achieve because you've made these relationships.

Exactly. You, it goes beyond that. You invest in the village, and you invest in the people, and they get to know you and you know them. You know what they need and what they want and yeah, like absolutely, you're right. You build up a very close relationship with people - there are people I'm still in contact with in that village, because the clinic is functioning. It's a vaccination center now, delivering babies. Later that year I delivered a baby myself up there when I was up there very late at night, I was needed - the midwife couldn't cope on her own. She needed somebody there to help. There was no light. The light had failed - times like that you realize just how important that clinic was and still is. Yeah, it was good. And we did other things, water systems, new pipe systems for the villages.

And the conditions you're often living in when you're there, you've told stories of bedbugs and fleas.

The fleas. The fleas… one of my real worst things, I did everything to avoid the fleas, but it was impossible. They just were everywhere. And you know, you'd go into some of the houses to have some of their milky tea on a cold winter's day and you'd sit on the - they were in their blankets. I mean, they're immune to them. But of course, they loved me and I, every now and again I'd have to go down to Islamabad to deflea and wash my clothes, and try and get some ointment for the bites. Oh, terrible, terrible time.

It's the kind of thing that could tip you over the edge, isn't it?

Oh, easily.

Dealing with those levels of stress. It's just the kind of thing that...

No, scratching yourself to death up there in a tent at night...oh, horrible. And you know, there was nothing to be done. I had flea powder everywhere, which is pretty toxic, actually. Stuff that you shouldn't really have, but I didn't care at the time. I'd have basked in it, I'd have swallowed it, I'd have done anything to get rid of them.

There were many, many interesting years in Pakistan, and other projects. And then flooding - we had flooding emergencies and I was up, I was back out for the flooding, and then I was back out to put another clinic in. One we built this time ourselves.

And landslides, caught in landslides, so many landslides and some very dotty times. Really, when I look back on it, it makes my spine shiver now. When I think what I got away with, really. I think I was very lucky. I mean, I have absolutely no religious, not a religious cell in my body. I think I was extremely lucky to get away with what I got away with. And other people didn't, some of our villagers lost their lives going over the track, you know, up to the village where the clinic was. Their vehicle got swept over by landslides. But I was never in a vehicle that happened to. We always managed to just stop suddenly before the landslide hit and reverse.... things like that.

Well, I know you've been in places where you've been ducking down low to avoid the crossfire.

Yeah, well that happened in Kosovo, one time we had to dive in between a load of big lorries because they were shooting across and trying to sniper the at the soldiers.

Where was the place you ended up, I remember you telling me this story where you were ill on the plane, and you ended up on this great long trek sort of semi-conscious.

I was hijacked by some Kosovo Albanians who were smuggling - I think smuggling arms into Kosovo. I think they were part of the Kosovo Liberation Army. I was on the plane, and we'd landed. I'm very, very sick. If the plane is turbulent coming down and I was so ill, I couldn't, I was virtually unconscious, and I got to the queue. They carried me. These four men carried me to the queue for the passports. Took my passport out my bag and I was carrying a lot of money - stuffed down my bra, stuffed down my knickers, everywhere I was carrying money. They took the passport, and they got me through immigration, and somebody was supposed to be meeting me outside, but I didn't know who it was. Somebody from the organization, but these four chaps just threw me in a car. Well, they didn't throw me in a car, they put me in a car. I was so ill...I was so ill, had all my bags and my money and everything and they took me through the UN border and because I am a westerner, I think I was probably very useful to them, because they kept saying this woman's ill, we've got to get her.

I was vaguely aware of that, and in the middle of the night we drove through the night. I don't know where we were going, and I ended up in some remote farmhouse somewhere in the middle of Kosovo. I don't know where it was, and I was so ill, I didn't care. I was put into bed with three children who were all asleep by this time. I don't know what time of the morning it was, and I went to sleep. I just slept. And then I woke up in the morning and I, well, I woke up some time in that day and I felt a lot better. I thought, oh my God, where am I? Where's all the money? Where's my passport? Where's my bag? Where is my luggage? Where's everything? It must've gone. I sat up and I got out the bed, and at the bottom of the bed was every single possession I came in with.

They put there, all the money, my passport, everything. And then within the hour, they'd given me some breakfast and taken me up to Mitrovica where I was working. So, there you go. You see, it could've been so much worse. How did I know? And I didn't care. I really didn't care. I just wanted to die. So - one has to have faith in mankind, I guess.

Maybe that helped in a way, that you were so out of it.

Maybe. Well yes, otherwise I'd have wondered what the hell was going on, I think. I'd have thought, well, you know, they would have taken money. Because I do remember vaguely that night they were unloading stuff from the boot and we were stopped at an army checkpoint, and they were looking in with a torch. The army, this is UN troops peacekeeping. I know these chaps were taken out and were frisked and I don't know how they got away with it. I wasn't really conscious enough to know. Yes, that was another interesting experience -- I'd forgotten about that.

You were in Greece for a time weren't you? With the...

When the Syrian refugees were coming across in the rafts in there, hundreds a day, well, thousands in a day. Yes. I spent two weeks there. That was very distressing too.

I bet.

Very distressing. The height of the Syrian war, little kids, little babies. The rafts would break, the engine would break down, and you'd have to run into the waters. They were coming in and they couldn't get in and you had to pull them in, and then you had to get them from some remote beach to some help center. And I hadn't gone out to do that particular job. I'd gone out with some money to offer it to a Greek organization that we were working with. But I ended up, I had this little tiny hire car and I was driving this little hire car over beaches, and tracks, and mountain roads, stuffed full of wet, drowning, Syrian refugees. And I don't know how many I managed to cram in my car each time. They were wet, they needed help. I was passing babies in through the window. Then I had about three in the front with me, this tiny car and I would drive them to a shelter and then I just go straight back down again for the next rafts coming in. Yeah, that was very distressing, actually.

So often we're so disconnected from the reality, the real human reality of what's going on. And it's just the immigrants - this group of immigrants, refugees. And they just become...

This amorphous group with long clothes, half drowned.

Exactly. And this is something we don't know and are labelled by certain journalists as cockroaches.

Yes, that's right. “Why are they coming here?”

But for you, you must, and anyone who watches the news can't fail to be hit emotionally by those pictures of little children. Eh. You know? But for you, it must have been so overwhelming to be there, in the thick of it.

Yes. I mean, the thing about that job, and I suppose the thing about my job is that you are so busy and you're so focused, and you have to think of the next thing you're going to do, that you don't allow yourself time to think, “God, this is terrible. I can't do this, this, oh, I have to get away from here. I can't bear to see another half drowned baby coming ashore crying for its mother”. And there's no mother because the mother's in some other boat or we don't know what's happened to the mother. You can't stop to think, you just have to act all the time. And I suppose that's what I've always done, and I certainly did in that situation. And you're right about the refugees because so many people who don't experience them close at hand fleeing from some terrible - the shelling in Syria was, was just ongoing all the time.

And they are teachers, they're doctors, they're nurses, they're it IT consultants, they're engineers. The ones I was bringing ashore, they were skilled people. They were, not all of course, not all highly skilled people, but so many were skilled people. Of course what gave it also a bad reputation was there's also a lot of Africans coming in from Afghanistan, Africans, Afro from Afghanistan actually I met, but they were Africans too. So they were mixed in with the Syrians. They know this became a bit of a problem because people were saying, well - when the Afghanistan - why are they coming in? They were fleeing the terrible, terrible war going on still in Afghanistan. I mean the Taliban were blowing people up, attacking everybody and you know, they were caught in the middle of it and they have no hope.

These people, these young people, Europe was their big dream. Well, I mean I don't think it turned out to be so good for so many of them, but...

They're often this tiny minority. I mean maybe there are few people who are doing it for some kind of choice or economical reasons, but I can't think how...

Economic migrants, yeah. I mean there were a lot of those, but most of them were fleeing conflict.

Yeah. But you know, the tiny minority in it, but they were all made to be, this is the majority. They're just coming. It's their choice or you know, they're terrorists or whatever.

Yeah, absolutely.

Actually the majority are just very normal people, desperate.

Desperate to try and get some sort of better life for their families. You know, it was, they're the children that were the driving force for these parents and, and they, they couldn't foresee any future for them and they could only foresee death or hopelessness.

Yeah. Cause you're not going to put your kids through that.

You're not going to take on that journey and pay all that money. The ones that really need -- the smugglers were obviously scurrilous. I saw them when I was in Turkey, and they would do anything to get money out of the refugees. The Syrians, they had quite a lot of money. In Syria, the life had been quite good, at a certain level, and they had money and they were bringing their money, and of course nearly all of that went to these smuggling groups, as it still does. We see it now happening from Libya of course. But that was another very -- I keep using the word distressing. There isn't really another word to use because when you see people in those situations, whether they're Palestinians in the West Bank having their olive groves torn down, or they're Syrian refugees trying to get into Europe through the Greek route to Lesbos, or Pakistani people in Kashmir after the earthquake, sleeping out under the open with aftershocks all the time and screaming.

It's all distressing, of course. Always distressing.

They're just people.

They're just people, absolutely. They're just people like everybody else here.

And how do you acclimatize going from that, to coming back home?

Well, that's always difficult. The coming home is always difficult. Very difficult, I find. I get used to it after a while, but I don't find the first couple of weeks very easy. I always find I don't relate to people, because people will come up and say - friends who come up and say, "Oh, you had a difficult time there. What was it like?" They are happy to talk for 15 minutes maybe and then say, "Well, he hasn't got a job yet, this son of mine." Or he hasn't got this or I don't know what to do about this - and you think...

Everything must pale in significance.

But it's a bit unfair on everybody because what's going on in their lives - it's very important. So you have to try and understand that. I do try hard, sometimes it's a bit difficult. I suppose I've got used to it now.

Lebanon has been particularly difficult. The Lebanon-Syrian border where I'd been working since 2014 - that's been our main focus. That's difficult because it's been very dangerous through 2015-16. Again, I think I was very lucky to get away with that. I was tagged a few times by the militants because I was a prime target for kidnapping. But never, gung-ho. People say, "Oh, it's a bit gung-ho to be there when all the other organizations had dropped out of the border towns". Because of the risk of the Islamic state were there and Al-Nuzra, they’d taken over the town. We did stay in and work, but I could only stay there for maximum, a week. I stayed 12 days once, and I think I was probably very lucky to get away with that. Several times I had to come out after two days. I was so protected by the Syrian team around me, they kept me safe. Without them, I don't know what would've happened - but we got a lot of work done. Was it worth the risk? Well, yeah, I would say worth the risk - but other people would say, "You're stupid. That would've been stupid if they got hold of you as a bargaining chip, that would have been bad". And it would, of course.

We balanced the risk very carefully beforehand - very carefully. And so, it wasn't gung-ho. It was a very considered managed risk. That risk is now more or less gone, it's much safer there now, but now we have other pressures. This year has been with climate... well, who knows if it's climate change, but the weather this winter has been horrendous. The worst ever weather they've had, so I've been out there three times for emergency weather related work, and then I've just come back from political pressure on the Syrians to be to be sent back to Syria, which would be a disaster for them. They've been destroying the shelters, the army have moved into destroy their homes - their shelter homes - and so we've had to try and help with that work.

I saw a post recently that you put up on Facebook, something about they had to reduce the height to be allowed.

That's right, for new rules. Crazy. Crazy.

Is that basically just an excuse to get rid of them?

Yes, it is, It's pressure on them to go. It's only in our town they've done that, where at the moment there's about 60,000 refugees. Over the last three years, the refugees have tried to weatherproof their shelters. So they built cheap cement walls around, or put cheap cement roof on because they've needed to. That doesn't mean they want to stay in Lebanon - the last thing they want to do is stay in Lebanon - but the government decided that anything with cement was a permanent structure, and they do not want them there as a permanent presence. So, they made a stupid rule how everything had to come down to one meter in height. The army said "If you don't do it, then we're going to move in with bulldozers and you'll lose everything". How could the disabled, which there are many, how could the elderly start to demolish their cement homes?

You need lump hammers and you need pneumatic drills and, they have reinforced with steel rods. We got a team of Syrians together that we had trained already in construction. We do a lot of training in construction, ready for their return, and they've got all the skills. We put a team of 15 together with our manager, Nabeel, and they went to the worst camps. The UN asked us to go to the camps for the disabled and the children's camps and the widow’s camps and do managed demolition - which is knocking it down without destroying their water systems and their sewage and their possessions. So that's what we were doing, then rebuilding with cheap, nasty UN supplied plastic sheeting and wood. So, come this next winter when the snow comes heavy, those shelters will collapse.

That would be very frustrating.

Very frustrating, yeah. We knew we were building shelters that would not withstand the next winter, or the next storm, really. The weather is changing there, the climate is changing. So, they won't be very warm, whereas the cement shelters were much warmer. So we don't know what will happen there, but at least we, you know, and that was fair. That was so distressing - elderly people would come to me and say, "We'd rather die. We'd rather die than have this happen to us, have our home destroyed. We might as well die. We can't go back to Syria, they don't want us here." And it's true - what do they do? And the disabled who didn't understand, a lot of the mentally disabled, did not understand what was happening, they suddenly saw their home had gone. That's still ongoing, the team is still working on that, still reconstructing. So yes, it's, it's been a very busy year this year.

Tell us a little bit and just briefly, about how Edinburgh Direct Aid works. I know you've explained to me before, it's a very different structure from a lot of the bigger charities.

It's entirely voluntary. We have a warehouse team in Edinburgh that works very hard filling the 40 foot containers, we send out two or three containers a year with clothing, with sewing machines, with looms, with material, with wool, with many things for women's workshops and for clothing, for the children's sports, clothing, toys, many things, basic medical supplies, although we're not allowed to take in much medical. They're all volunteers - the whole team is volunteers. We have a Treasurer, and we have two Fundraisers, and we have the Chairman who is 91 years old and still running 10 kilometers to raise funding for us - and it's just run as a big family. I'm their main field person that goes out. Sometimes other people do go out, but I'm obviously the chief sort of Field Officer. So that's how it's run - just purely on a volunteer basis.

But what that means on a practical level, is that people who donate - all that money gets used.

It does, yeah.

Rather than with one of the bigger charities…

Yeah, that’s right.

…where a big chunk of that presumably…

Yeah

I’ve no idea what kind of percentage, goes on wages and all sorts of things.

No, there's a few stories about that, but I won't go into that. I don't know what our percentage that goes straight to the beneficiaries is. It's very high, because also we try - I can't always fund my own expenses for travel because I'm out there so often, I can't. But I do when I can, because I don't have much of an income really. Others that go out, - we have a retired doctor, and Dennis himself, who's a retired mathematician, and some others who do occasionally go out, everything is funded by them. Nothing comes out of the funding - it's all personal expenses that they pay themselves. That is very different to how most organizations would work. And of course, there's no salaries or anything. We don't get paid anything, it costs me some money during the year to go out, but I do get some of that back because I can't simply afford to keep doing it. Some four, five times I've been out this year. So you've got flights to Beruit, and yeah, that's how it works.

So it's a small charity, but actively speaking has a big impact.

Big punch - I'd say we have a fairly big punch for such a small charity, and somehow the money just keeps coming in. It's endless fundraising events that are very hard work. I don't do the fundraising - I do talks, but I'm not big on the fundraising side, and I think that's just as hard a job as what I have to do when I go out to the Syrian border. Fundraising is a nightmare, and we just rely on regular donors - some businesses, sometimes the Scottish government gives us some money. We have a very good reputation, I think that's how we keep the money coming in. So - long may that continue!

Well, thank you for sharing some of your stories. Like I say, I've wanted to share them for a long time. When I heard you were here, I grabbed the opportunity.

It's always a good opportunity for having my little relaxing holiday here now. Yeah, absolutely. It's nice to tell the story of what we do.

And so what might be a top tip that you could share with our listeners? It can be anything you like.

Well, I suppose in the end, it would be what I've always said - even when I wasn't aid working, when I was on my year long trip around South America and getting into all sorts of scrapes and difficulties, and Tiananmen Square and the massacre and I got caught in so many things.... It would be that no matter how bad things are, somebody somewhere will come along and help you out. Always, somebody will be there to help you out. You've just got to have faith that that will happen. Just when you think there is nothing that's gonna get any better, and you don't know what to do, and you're really stuck, somebody comes along. There's always a solution from another person or people. I would say that that's probably my top tip - always think something will come along. And it does.

And you did mention earlier that you have this underlying faith in humanity that probably, may be what helps you get through some of those sticky situations.

Yeah, I think so. Absolutely. Even talking to a member of the Islamic state once by chance, I didn't know he was - he was a very fluent English speaker, protecting his family, was going back to Syria to die. We had a really interesting, nice conversation. Not that I'm supporting in any way the Islamic state did, because they are really terrible. Maybe he was just a slightly different version of that, you see? So yeah, faith in humanity always - I think we have to have that. Definitely.

Well, thank you very much Maggie, it’s been a great pleasure.

Thank you.