Originally published at: https://ketowomanpodcast.com/bec-johnson-transcript/

This transcript is brought to you thanks to the hard work of Cheryl Meyers.

Welcome Bec to the Keto Woman podcast. How are you doing today?

I'm doing really well. Thank you Daisy. Thanks for having me.

Loving the conference?

It's awesome. I'm learning so, so much, my brain is full.

Mine too. It's, it feels like there's a little bit of space there left to maybe squeeze some more knowledge in, but I was just saying earlier before we started, I sometimes feel have this sort of limit to how much you can stuff in, in a limited period of time. But you made the comment and I think that's absolutely true that they've got a really nice pace with different presentations going on that that just stops you having that overload effect.

I agree. I think that they've balanced the high level public health content with the getting down into the weeds with the technical stuff really well. So you can come through a technical presentation and just have a little bit of a break and zoom out and take on something that's a bit more big picture. I really like the way they've balanced that.

Yeah, me too. So tell us a bit about you.

I am 35 years old. I've had Type 1 diabetes since I was 17. I've been eating low carb for about 17 and a half years. So seven or eight months post diagnosis, I switched to a low carb diet and have been Keto since about 2012 when I started experimenting with a Ketogenic approach for endurance exercise. I'm also the CEO and one of the founders of the Type 1 diabetes family center in Perth, in Western Australia. And that's a facility and service of which I'm immensely proud.

We're now supporting more than a thousand people impacted by Type 1 diabetes in our state. And we very much have an holistic and food first approach to diabetes management encompassing not only nutrition, certainly, but insulin therapy, being versed up on all the tools, the technical tools and devices that you can use to manage diabetes, but also mental wellness, peer support and very much that wraparound social support element that I think is needed for a life well lived with a chronic disease like diabetes.

I think it's really important to take that holistic approach.

Absolutely. And I think that we've had a very medical model of care for Type 1 diabetes that's really focused on insulin therapy and insulin delivery devices. And I feel that zooming out and looking at all the different pillars of good diabetes care and good health and nutrition, exercise, mental support, and indeed family support. That's why we called ourselves the Type 1 diabetes family center as far as I'm concerned, Type 1 diabetes is a team sport. Every person in a family is impacted by a diagnosis, and every person needs to be knowledgeable, compassionate to the person living with diabetes but also to themselves because it is a long journey and it can go on a lot of different directions and the family center is there to help people through that.

And it's great this working together with the patient and their family, which is really important, but with the medical care they're getting. I was talking to Belinda Lennerz earlier and she was saying that there's often this mismatch between the patient and the practitioner they're working with and that they're quite often feeling really alone because they're going out on a bit of a limb getting involved in this way of eating and then not feeling supported. So it's really nice to hear that there are more practices at least embracing this approach even if they can't necessarily promote it, but it sounds like you're able to take it more to that level to actually promote it and suggested as a way of eating and a lifestyle to adopt that's really going to help manage the lifestyle for the Type 1 diabetic in question.

Yes, we are, we believe that a low carbohydrate approach should be on the table as one of the first line therapies in relation to Type 1 diabetes management. Obviously it's always going to be adjunct to good insulin therapy. However, we're not afraid to talk about it. We feel that it is not that controversial. It's just eating real food. And it is certainly central to our approach to care. If patients want to come in and talk about it, then we'll have the conversation because at the family center, we believe that people with Type 1 should be supported to transition to or maintain a low carbohydrate approach with solid dietetic support. They need to be meeting their micronutrients, they need to be meeting their energy requirements. And I think that not everybody does it well alone. And if we're able to provide them that clinical support, then that's what we're here to do.

We are not necessarily leading with it. We lead with the holistic approach that I think the patient-centered approach is really what we're about, in that when patients come into the family center, the first question they're asked is what are your goals? And we really work with those because if somebody comes in and, HbA1c isn't their goal and it's not their focus, but perhaps weight management or exercise or managing hypos is, then we've got to go in building a relationship on what they need, rather than necessarily going away and say, well HbA1c is the marker of good diabetes management. That doesn't necessarily serve them. So, that's what we do.

And what are the most common concerns that people have when they come to you? The primary concerns, the things that are impacting their lives in the most negative way that they're trying to fix or find strategies to help, you know. What are the most common problems that people are asking for help?

In relation to diet and Type 1 diabetes or more generally?

I suppose generally, because you take that holistic approach in just managing their Type 1 diabetes. What are the biggest issues that they have that really impact living a quote/ unquote normal life?

Before we opened the family center, we ran a whole series of focus groups asking parents of kids with Type 1 and adolescents and young people with Type 1 what they needed. And the theme that came through most strongly was connection. They said to us, we feel isolated. We feel alone. We feel unsupported and underserved by not only the medical community but by the community at large. People don't understand our disease. It's invisible, which is in some ways a blessing and in some ways a curse, because the general community doesn't see it, doesn't understand it. And the power of connection is transformative. And that's why we have very much led with a peer support approach.

We've set up online communities that are thriving with parents of kids with Type 1 and now adults, and they're running through closed Facebook groups. And as you're known as someone participating in the social media world in relation to Keto and this way of eating, it's just a live dynamic community. And so we've set those up. We have hundreds of engagements every day through our online communities and we also have a lot of face to face connection and events. So that's how we have tried to build a community in Western Australia, our own people with Type 1, because we want to make sure that people don't have to live that lonely road, and that they, they can feel connected. And I think the value of connection is not only in the sense of not feeling isolated and alone, it's also the information exchange that happens when you're part of a bigger community, the hive brain that you can tap into of hundreds of people that have experienced what you're experiencing and can offer insight and advice and knowledge. I think there's huge value in that as well.

That's a really big difference, isn't it? I can remember when I had my first weight loss surgery and I was just completely isolated and just couldn't do it, wasn't getting good information from the bariatric team and there was just nowhere to access the information until I started finding online groups, you know, and that surgery didn't go well, but when I had the revision surgery, I had access to all these online groups and the difference was incredible. Being able to make contact with people who are going through, have been through the same thing. It's just worlds apart from dealing with the theory of it from someone who hasn't experienced it. It's just so much more reassuring to be able to, to talk to your peers in that situation isn't it?

It absolutely is and we've made that central to the philosophy at the family center in that nearly every member of our team is personally impacted by Type 1 so it goes all the way through to the people. I truly believe that people with Type 1 diabetes should be working in diabetes organizations because there is that sense of, again, connection. You can drop your shoulders when you walk into the family center because everybody there gets it and that ocean deep compassion, that's the stuff. That's the stuff that changes the trajectory of people's Type 1 diabetes management that helps them come to terms with it, to make peace with it because they see others who are living with it and working well with it. And I think that's what we aim to create.

I'd be really interested to hear more about your personal experience about when you got your diagnosis. What led up to that? What led up to you know, you obviously realized that something was going wrong, there was a problem, but I'd just be interested to hear more about that.

It was interesting. It came off the back of it very, very stressful year. I had finished my final year exams and I was the goody two shoes over achiever at high school who was the captain of everything. And I had, I believe that maybe that lead in of that sort of eight to 12 months of high stress in my final year at school, was possibly one of the triggers of my diabetes diagnosis, which was in April the following year. So I got a really unwell over a series of, you know, short months and lost a lot of weight. I think I lost 12, 14 kilos over a couple of months. Started—the thirst is just indescribable, and I remember I would wake up through the night and probably I drank the worst thing I possibly could have drank. I still couldn't, I couldn't even go near a glass of it today. And that was apple and guava juice. I went through liters of the stuff! And indeed I remember being at a wedding, and that night I was so thirsty, I drank five carafes of lemonade. I mean, and I, I remember the fellow I was with thinking, what is wrong with this girl?

And I was just making my sugar level higher and higher and higher and getting thirstier and thirstier. I had every symptom in the book, blurry vision, sores that wouldn't heal, leg cramps—and finally my mom dragged me to the doctor. I had, she had made several appointments for me, which I had canceled cause I hate going to the doctor. And I went to see my GP who did a finger stick. And, actually no, he did a blood draw and I got a phone call the next day and I'll never forget his voice. He said, 'Rebecca, you have diabetes.' And it was his very final sentence. And my heart sank. I didn't really know what that meant, but I knew it was bad. And he basically said, get to the hospital asap. And I went there and I was diagnosed and it was just this whirlwind of three or four days. I was admitted. I was given my first insulin injection, which made me feel instantly better, which was wonderful.

But then I was given the education and I will never forget again, they gave an brought in an orange and a needle and they made me practice learning how to inject with the orange because it's the same sort of texture as flesh, apparently. So I injected a number of times and then they gave me a fresh needle and said, okay, now it's your turn. And that was it. That was the start of five to seven injections of insulin every day. I think on calculation I've probably had around 45,000 injections in my life. It was the start of eight to 10 blood glucose finger pricks every day. And it was the beginning of the counting, the endless counting of carbohydrates, fats and proteins, plugging that into complex insulin to carbohydrate ratios, which change in my body four to five times a day. The string theory that you have to do to manage insulin dose calculations. And I guess the beginning of that fear, which lasted in a very intense way for the first eight months, of administering a hormone that is so powerful, it will kill me if I get the dose wrong in what back then was in really quite large amounts and had me afraid to take a walk around the block.

That's incredible.

Or to go to sleep or any of those things that are normal life we should be able to do without thinking. And that was the beginning of my journey towards finding a solution.

Yeah. So what advice were you given when it comes to diet?

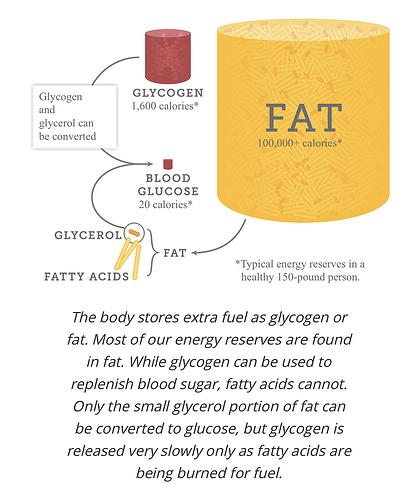

Eat according to the Australian guide to healthy eating, which was, you know, 8 to 12 serves of starchy vegetables and grain based carbohydrates every day. Limit fat, lots of fruit and I did, I dutifully did that for the first eight months. It was cereal and toast for breakfast. I had sandwiches for lunch, I had fruit for snacks. I had pasta for dinner and every meal, my blood glucose surged high and then crushed low because insulin is a woefully blunt tool. Synthetic insulin in any case, it is not even close to the sensitivity of a physiological insulin response. So I was trying to deal with these tsunamis of glucose charging into my system with, you know, great big wads of exogenously delivered artificial insulin and a lot of guesswork.

That's what strikes me—that the calculations are just fraught with danger because they can only be guesstimates at best.

They are. And I think that we're given this advice as people with Type 1 that here is this thing called the insulin to carbohydrate ratio. And if you count your carbs accurately and you weigh them and you'd do the ratio, then your dose is going to be good. And I really genuinely think that many members of the medical profession believe that works. It's not sound science, it's much more art than it is science because there are so many factors that influence not only the carbohydrates and the rate at which they're absorbed into our system, but also how fast insulin is absorbed. I know from years of practice that if I put my needle in my stomach it's going to work a lot faster than if I put it into my arm. And if I put it into my bum, it's going to work in a different way altogether.

And so even just the basic where you put your needle in is going to impact how fast the insulin works. And then there are myriad other factors around absorption of tissues at the site, you know, how active you've been. I think wonderful Adam Brown has isolated 42 factors that impact blood glucose and a lot of them are food and obviously insulin related. But it is, it is just such a complex beast, and the advice that you're given that here's the formula, go forth and conquer. It just falls flat. And yet I think so many people, it raises this false hope that "We've got, we've got a tool, we have a formula," and it just doesn't work like that.

There are just variables at every level, every turn. But yet you're being told that this is quite an accurate linear equation that you should be able to master. So if things aren't going quite right, which I imagine is probably the norm or certainly not going right all the time, the logical conclusion of that is well, I must be doing it wrong.

Absolutely. And there, I think the feeling of I am a failure is a very familiar feeling for people with Type 1, because you know, we're set up to hope and believe that with the formulas and with the counting, you know, we've got this control over diabetes and that doesn't work. And then when we go in to see practitioners around it who aren't compassionate to the daily experience of living with Type 1, it can feel like you're a naughty kid being dragged in front of the principal. You know, they're there. I remember going in to see my endocrinologist and he would flip through my diet, my book, you know, there's apps for this stuff now, but I used to write down all blood sugar levels and, and I might have fantastic control for weeks, but then he'd flipped back and he'd point to the hypo that I had on the 7th of April, which is months before, and he said, what happened here? And the whole appointment many times would be zero in on something that went wrong and reverse engineering that. And so there is never a sense—well there wasn't in my experience—it wasn't a sense of congratulating me or celebrating me for the things I did right. It was more around, okay, how do we hone in on the risks and that and the stuff that I didn't do right.

And I think the hard thing about Type 1 is that it's all on me. All of those calculations, all of the discipline around food, around exercise, around managing those myriad factors, it's all on me to manage. There's no other thing I can blame. And so when it goes wrong, it does feel like my fault. And that can be a really hard thing to deal with. And learning more recently around self-compassion, and building that resilience and, and compassionate self-talk and behavior has been a really important piece for me and a relatively new thing. But we have to be compassionate to ourselves because there's a lot of management that goes into diabetes at any given moment. 25% of my brain space is taken up with calculations.

Got to allow some room for other things. What triggered, led you to start looking for something else? A different way of managing all this?

There wasn't a particular incident. I just woke up one morning and said, I can't live like this, I've had enough. I there has to be another way. And I think I went, it wasn't Google then, I went online and found the Dr. Bernstein “Diabetes Solution." I wish I could remember the search terms that I plugged in to find that, but I saved up, I was working in a video store as a student at the time and I was earning $11 an hour and I had to save up, I think it was about $68 to buy this book and pay for the shipping. And it took weeks to come from America. There was no Amazon or Book Depository then. And I read it, I devoured it and it made so much sense in indeed I had already been restricting carbohydrate in the lead in to getting this book because I just couldn't cope with the high, the feeling of my high blood sugar. And then reading that was very much validation.

So I took those high level principles I felt much more confident about it and implemented them into my life. And almost immediately everything changed. My insulin dose has dropped by 75%, and they still remain very, very low. So my error margins dropped significantly because I wasn't, dosing myself with industrial doses of insulin anymore. My hypos became mild instead of completely brain frying, you know, shaking, sweating, terrifying things. And everything became so much easier. My roller coaster blood glucose levels smoothed out and I have maintained that way of eating, with a few blips, admittedly, for the last 17 and a half years and maintained A1Cs in the low fives and high fours. I think my highest A1C ever was 6.6 for the majority of that time. It has completely changed my trajectory, with this disease and my ability to live a rich and full and active life with it.

Yeah, and I can just sense that switch from despair and I just can't do this anymore to one of hope and potential of happiness and normality.

Absolutely. And people say, Oh wow, but isn't eating low carb hard? I think it might take a bit of discipline. I find it extremely easy now, and a bit of creativity in the kitchen.

It takes some discipline to start with.

Yeah, I agree. It takes, you know, build your knowledge base, get committed, be disciplined around navigating your food choices and you know, get creative. Although it's getting easier and easier now. It wasn't easy then because they were no low carb conversations happening. I was very much out in the wild. But it is something that we can do and we can thrive with. And you're absolutely right. Once you have that foundation and that base laid around the confidence and the skills to eat low carb and navigate food, then it becomes so much easier and life does feel more hopeful.

I was at a party last night, Pamela Zorn had laid out a wonderful array of food and we were just laughing, you know, joking saying this, this way of eating is so onerous. There were two or three different kinds of crackers, there was a delicious smoked salmon dip. She'd made cultured butter, cultured truffle butter, poppers, prime rib, smoked chicken.

Where was my invitation?

Is so hard. How can anyone think eating that is onerous in any way? Yes, the transition is difficult because apart from anything else, you know, most people are just fighting that carb addiction. But once you're through that and you can just revel in so many things that we've been told for so long are bad because they're full of fat, but they're delicious.

Yes, yes.

But you're a swimmer, a competitive swimmer.

That's right.

Tell us about that and how that all the implications of that with the Type 1.

I love swimming. I've been swimming since I was a kid. And I'll dial back a little bit into sort of transitioning across into Keto because it has been, I had to take a long hiatus from swimming until I really got Keto right, because for various reasons there were difficulties, technical difficulties around testing my blood glucose in the water. But also the transition across to Keto in 2012 was around endurance exercise. Generally. I was doing long distance mountain bike racing at that point and triathlon and the conversation around ketogenic diets and becoming fat adapted sort of came across my radar with Steve Phinney and Jeff Volek's book, "The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance." And that really changed my thinking around how I could become a better endurance athlete by becoming completely fat adapted.

At that point I'd probably been low carb, and eating above the Keto threshold. When I read that book, I dropped my carbohydrate considerably and change my macronutrient ratio and found myself racing around mountain bike courses with a big smile on my face and endless energy. And that really helped me feel safe and confident to come back to swimming because I felt having watched my blood glucose stay completely stable while I raced and trained on land, I felt confident that I could get back in the water. And at that point, because I was not able to test my blood, I could still trust that it was going to stay stable. So that was really the push that I needed and certainly wanted to be able to get back into swimming. And I have since gone on and done the Rottnest channel swim twice now, which is a 20 kilometer swim to an island off Perth.

We've got a few big plans to do a double crossing next year. So that would be a pretty major achievement that I'd really love to tackle. But we do a huge amount of training, so squad sessions, sessions in the river, sessions in the ocean every week in the lead up to these races. And yeah, fueling it with a ketogenic approach. It's quite remarkable when I see my swimming friends who are taking on carbohydrates every 20 minutes while we're training and gel shots and we're having to drop drink bottles with PowerAde right up and down the beach when we do our long sets and they all remark, you know, how do you do this without any fuel? And I think I've got enough fuel in my left bum cheek to swim to Madagascar and it feels wonderful and very freeing to not only be able to feel like I have an endless source of slow burn energy, not have to eat because—eating while swimming, I don't know if you've ever tried it. It's not an easy thing to do—

I can't imagine it would be, no.

—when you've got a salty tongue and you're tried to ingest something while you're treading water because you're not allowed to hang onto a boat that's against the race rules. It's, it's not a fun thing, you know? And I've got mates that ate peanut butter sandwiches and all sorts of ridiculous things out there and they're great. I'd rather just keep swimming, thanks. But also finally to trust that I can, my blood glucose is going to say stable. That's the holy grail of exercise formulas for someone with Type 1. So it's something that ketogenic diet has very much enabled me to do and, and to do well, which I'm really happy about.

I can still remember my mum used to drum into me that I wasn't allowed to swim until at least an hour after I'd eaten. So I think I'd constantly have that voice in my head. Well, you can't possibly eat and be swimming at the same time.

You'd have to take a little rest, a siesta floating on your back. I don't actually understand.

I don't know where that has come from either. But it was just something that was this really strict rule.

Yeah, I've heard that too as a kid. So I don't know about that.

Presumably then you must have seen quite a difference with the practicalities of how you were organizing that your swim before and after Keto. It sounds like you're not having to take on any fuel at all, you know, in the competition swimming or do you have to take on some?

I could very easily do it completely fasted. I guess the only reason why I need or I would refuel during a long race is if I get a bit hungry or to lift my spirit. Because if you're face down in murky green water for hours and hours on end with no one to talk to you and just inside your own head, sometimes it's nice to take a break and having something nice to eat is, or take on board is just something to do. I think the other reason why I might take some nutrition in is to keep me warm and that does actually really help. Yeah, there's no real need for it. I can run on ketones and feel like I've got perfectly stable energy levels throughout long swims.

But you did need it before, pre-keto?

Pre-keto, I was doing a little bit of swimming, but I think that at that point I had a lot less knowledge and the skills weren't there in relation to how I manage diabetes and I wasn't doing particularly well, which made me sort of avoid swimming to a certain extent, the testing regimen was a lot more onerous. Now I wear a Freestyle Libre, which is the little sensor I can put the receiver in a waterproof phone bag and just scan myself in the water so I'm totally self-sufficient. Then I'd have to stop and dry my fingers and get warm and test my blood and it was just fairly onerous to do. So I think that combination of the technology and the ketogenic approach is really just allowed me to do swimming with the freedom that I want to do it with without having to constantly think about or be anxious about blood sugar levels and how I'm going to test them next.

I remember Richard Morris telling me about the practicalities. You have to have the insulin you potentially need floating out there, accessible for you to use when you need it?

Yes. So, when I race, I have a paddler, a support paddler and he would have my hydration, nutrition, insulin or preprepped, my glucose monitor in the Libre. And when we stop to do a blood sugar test, he will throw me Libre. I can't touch the boat. I've got to tread water, scan. If I made insulin, he's got the pens, he has to throw that to me. It's got a float on it so that it doesn't sink because I can't even be passed something because that would be a disqualification. I have practiced treading water and injecting insulin. It's not as difficult as you might think with a pen in particular. And yeah. So all of those transitions have to be practiced before race day to make sure that we're doing it right. I'm not going to be disqualified and I can do all the diabetes management tasks that I need to do.

What's the distance? How long are you talking about with these races and the time that it takes?

We would do 10 kilometer swims regularly on the weekends and the distance for the race, this recent one's 19.7 kilometers. So what's that? About 12 and a half miles, I think. The first time I did it was horrific. It took nearly 10 hours. I got stuck in a horrible current and I swam over the same rock for about two hours, at one point I think it was soul destroying.

I was going to say, that sounds like the ultimate in frustration.

It was awful and I was seasick and I didn't know that I got seasick until about 10 k's in, when I started being sick and my heart just sank because I thought, oh my gosh, I've got a long way to go. If the only thing that's going to fix me at this point, because I can't keep anything down, is being on land and I have 10 kilometers to swim. So that took me six hours, that last 10 k's of that race because of the current issue. And because I had to stop every 15 minutes to puke. But if not for keto at that point, if I had of been a carb dependent athlete and I needed to have nutrition going in every 15 or 20 minutes, that would have been my swim over, you know—and I trained for six months for this race.

But the fact that I didn't have to take anything on board as I was being sick, that was something that I was thinking far out, I'm so glad that I've adapted to this approach because I just don't need to have the fuel. It's awful vomiting, but I can get through that. The second time I did it, which was last week, it took me seven hours. So I took three hours off my PB, which I'm really happy with. You don't do that every day. And it was a brilliant swim, I had a great time. I had a tiny little bit too much long acting insulin on board, which I started to really wear in the last couple of hours of the race. So I did need to take some glucose on to counteract that. But again, first 14 k's was a breeze. I had half a YoPRO yogurt, which was three grams of carbs just so that I could take some medication on board at the 10 k mark and more sea sickness tablets. And that was all I would have needed if not for that tiny little bit too much insulin. So I felt a lot better through that race.

So you're out there apart from your support team, you're out there on your own. Multiple people are racing but yeah. So all on your own

Yeah, the Rottnest Channel Swim is an iconic event in WA [Western Australia], they have about two and a half thousand participants, not all solos. There's about 300 odd solos that attempt to do it each year and the rest of doing it in duos and teams. So it's a busy race. It thins out a bit in the middle, but very congested at the start and the finish, I don't think I would swim to Rottnest just on my own. I like the safety in numbers concept as you may know, WA is also the shark attack capital of the world at the moment. So I think that I'm, I'm happy to be in the mix there, but it's a lovely swim. You can see the bottom the whole way. And it really is a stunning environment.

You've mentioned a few times how things were when you were first diagnosed and the technical advances in things that are available to you to help you manage and monitor this. Perhaps you could just share a little bit about the change that you've seen over the years that you've been dealing with this.

When I was first diagnosed, it was obviously a blood glucose monitor. That's the only technology that was out then. And I used that for many years. Indeed, I still do when I had to take breaks from the Libre or CGM. And obviously that's evolved to continuous glucose monitoring and the Libre Flash glucose monitoring devices. I think both of them have been absolute game changers in Type 1 diabetes care. Unfortunately they're not as affordable as they need to be for the Type 1 community. And that's something that they're suddenly changing to a certain extent in Australia. They are now federally subsidized for people under 21 and fingers crossed that they subsidize them for adults as well. But the visibility of blood glucose levels is something that when we work with people at the family center, the lights go on when they see the blood glucose surge that happens after they eat carbohydrate.

It's instant. When I was diagnosed, and indeed even now, the advice, I still hear that people are told this, I was actively discouraged from testing my glucose after meals. I was told test before, so before breakfast, eat your breakfast and then don't test again until before lunch. And of course in the meantime, my blood glucose would have gone up to 15, 17, 20—and it would come back down very nicely into range and I might be 5.6 before lunch, but meanwhile I spent three hours with my blood sugar level out of range.

What was the reasoning for that then? It doesn't seem to make any sense—you would've thought you'd need to know what was going on in-between?

Well, the rationale would be it's going to happen anyway. And if you know about it, you want to correct it with more insulin and if you correct it with more insulin and you end up in a hypo because there's going to land in the safe range, it be all right.

That is obviously that linear equation, again, that doesn't exist...

Well it just disregarded the three hours after every meal that I would spend outside of range. And if I didn't know about it then I couldn't even act on it. And at that point, the only, apart from reducing carbohydrate, I could change the time I took my insulin, take it a little earlier. So it married up with the carbohydrate curve perhaps as a mitigating strategy. But I wasn't even given access to that information. And it took me becoming an overzealous blood glucose tester to the point where I had to have letters written by my doctor to the National Diabetes Services Scheme, justifying why I needed so many blood glucose test strips because people thought, I think they thought I was selling them on the black market or something. Because I was doing 20 tests a day cause I just needed to understand.

So CGM—now people, it's visible. You know, we've got 288 glucose readings a day and it's just sensational information. And I think that people really have the tools now to be able to act on that and change their management strategies to adapt their food and their insulin therapy due to better manage diabetes. That's glucose monitoring technology. Obviously the insulin pumps have come a long way. I don't use one, but I see their benefits particularly in children. Kids need that flexibility I think around being able to manage insulin and basal rates according to their very sporadic levels of activity. I think as adults we can be a little bit more structured about activity choices. Whereas kids, I think, you know, type Type 1 diabetes already feels like a straightjacket if they can run and play when they feel like running and playing and we can just drop their basal rates, I think that's fantastic.

The other thing I think the benefit is micro bolusing. The pumps give the ability to bolus and indeed run basal rates at much more sensitively fine-tuned doses than you can get with a syringe or a pen. There are real benefits to the pump. That said, there are also the downside. Wearable technology has mechanical issues, you know, pump fat failures, bubbles in the line. All the things that happen that come along with pumps that people need to think about as does CGM. It's very intrusive if you've got a phone or a device alarming at you all the time, especially if you're trying to run really tight thresholds, you will hear alarms often. It will interrupt your day and your sleep and your thinking. And that's one of the pieces that I think that we don't do very well in Type 1 diabetes care is prepare people for the psychological burden of the wearable devices. The very active wearing a piece of space junk our kids call it on our bodies and getting the questions and the curiosity from the community at large and have to explain diabetes over and over again. That can become a real drag. So there's light and shade around technology, and I think we have to be really careful in the way we talk about it because in our diabetes community pumps are almost incentivized. I hear this thing of when we get to the pump, like when we graduate to a pump,

Yeah, this is the goal for everybody.

Yeah. And a pump is just a glorified insulin delivery device. You know, it might be snazzy, but it isn't going to change the fact that you're still making all the decisions. We do have closed loop technology that is just starting to be released, which was really exciting. So that means a continuous glucose monitor is talking to the pump and automatically adjusting basal rates. The person still has to think, they still have to do meal announcements in exercise announcements. So they're actively managing those variables.

Yet the tendency is to think that it's all just going to be automated and they can, the worry goes away because the responsibility is taken on by these interacting machines that are just going to manage it all for them.

Indeed. And that plays out both in the community at large, where people, every time there's a big news article, Oh closed loop technology, somebody rings me up and goes, they've got an artificial pancreas now—your problems are all solved. And you know, that's absolutely not the case. And then within the Type 1 community, when we see the research plays out, when you put people on pumps, their A1Cs in the first 12 months often going up because they themselves think, ah, I'm on a pump now, it's all automated. And so, and that's a bit of a hard reality when they realize, Whoa, actually I still have to do the inputs. I choose not to use a pump primarily because there are no pumps that are waterproof. So that's a little bit of a struggle for me. But also because I've found a really great regimen with the insulins that I use and I feel like if it ain't broke, don't fix it.

Interestingly, I have a retro thing going on with the insulin that I use. So when I was first diagnosed, there wasn't any rapid acting insulin. I was put onto regular human insulin, which is now considered so old school, you know, pharmacies don't stock it. When I asked my GP for it, he looked at me like I had grown a second head. You know, why do you want this old insulin, over the years, over the time I progressed to the newer analog insulins for a period of time there. But I've since come back to using R, the regular insulin, in the last few years because it's remarkable in how the time action profile and the peak of R insulin marries up with a protein glucose spike that I get. So protein spikes my glucose after four to five hours and that is exactly the time when R peaks. So, it's really interesting that you know, we can actually look to the older insulin technology and find it useful in this new way of eating.

That is interesting. I found it interesting as well what Jake Kushner was saying about how potentially these automated systems with the insulin pump, how it potentially could work particularly well if you were eating low carb because you had, the blood glucose ranges were moving in a much tighter band.

Yes. And the increases are not as sharp. So if you're eating a mostly protein and fat based diet, you'll have sort of these mild peaks and that's something that the pump can keep up with so that the pump can actually automatically adjust a basal rate rather than requiring a big bolus of insulin in order to keep up with that protein and fat curve. And I think that, I mean that is really the ultimate hands-off diabetes management. I mean, you're not actually having to actively put meal announcements or food announcements into that pump, which is almost, I mean, I hate to say the word cure, but it's certainly lightens that mental burden, which is one of the hardest things to bear with diabetes.

Yeah. So it feels like, instead of having to do that micromanaging throughout the day, if you more macro manage, pun intended, I guess, with your overall diet. And look at focusing on that. But that's not having to look at the details all the time. I can see that being quite freeing. Obviously you've still got to carry on paying attention, but you're managing it with more broad brush strokes and maybe this technology and equipment could take care of those finer details.

Absolutely.

It can free you up a little bit more for day to day living.

That's the ultimate application for the closed loop system. And indeed are you familiar with the We Are Not Waiting movement?

No.

The We Are Not Waiting movement created a technology initially called Nightscout. It's open source. It's created by citizen scientists, mums and dads and people with Type 1 diabetes around kitchen tables around the world where they hacked continuous glucose monitors and firstly worked out a way to bounce the information to phones for remote monitoring. Awesome. Especially for parents. The next step has been the development of the open artificial pancreas system and the loop system. So these are again hacked systems where people are essentially running the closed loop type technology and have been for a number of years now well before the companies have released it. I have a friend at home, Kyle Masterman, who is a sensational athlete, low carber and he's running an open APS and he has messaged me a number of times and says, I haven't given myself a bolus all week.

And the system is just running in the background and managing things for him, and it's giving him these micro boluses of insulin as he eats a big protein meal, you see the insulin start to catch up and his blood sugar level is insanely good. The thing I think the system hasn't quite adapted to, is exercise yet, and that's the next piece. But the idea that the food variable and the insulin variable can run in the background. That is awesome.

Yeah, I think that sending the same way when we haven't spoken too much on that, but the tendency is just to look at food. But it sounds like looking at your activity level is hugely important.

I've worked out over years of experimentation than any exercise that spikes my heart rate over about one 80 beats per minute is going to raise my blood sugar level. So I actually need to take insulin in order to do high intensity interval training or spin class or anything where I'm going to do sprints. That's so counterintuitive. I need insulin to exercise. Hang on a minute. The other thing that causes my blood sugar level to go up is glycolytic exercise, like lifting. Then the opposite effect happens if I'm doing longer, slower endurance stuff. If I've got the formula in my basal insulin dose right, and keeping in mind that I inject that, you know, I've got, I'm committed for 16 to 18 hours of a certain activity level once I do that. So sometimes it's seven o'clock in the morning, I take a certain dose and I do a different activity than I anticipated in the evening. And sometimes you can get that wrong, but if I've got my basal conditions right, then my blood sugar level with endurance exercise normally stay stable.

If I've got it wrong, sometimes it will drop off a little. So that seems to play out as a general assumption for most people with Type 1. High intensity—blood glucose spike, low intensity—blood glucose is stable or drop. And bringing that into play is really important. , because when you're dosing insulin, you're not only dosing on what you're about to eat, you're also thinking how much activity have I done in the last three to 24 hours and how much activity do I anticipate doing probably in the next three to eight hours. And so as you say, you're bringing in another set of variables, the duration, the time, and the intensity of activity or another few variables if you want to really drill down into it that you have to consider.

It sounds like you have to be super organized and good at planning.

Absolutely. I think that's something that diabetes has taught me. It's not my strong suit, but amongst a whole lot of other lessons, being a good planner. And I think almost to the extent where that too for a while it took over my life about planning and routine and I would become very anxious if my routine was interrupted and started to try and build a little bit more, I guess being able to be a little bit more relaxed about changes to the plan has been again, a more recent project.

Well, I could go on talking to you for hours. We're being ushered and nagged by—interesting enough, the room needs to be set up for an exercise and movement session. I like to round off the podcast with a top tip, which can be anything you like, but I think maybe it would be nice to give your top advice for somebody who's just been diagnosed with Type 1.

Connect with community. Clinicians took me some of the way—the community took me the rest of the way. If you have access through online groups or face to face support, other people who are walking a mile in your shoes, the information exchange, the support and understanding that you will get is the key to not only understanding diabetes well, but making peace with diabetes. And I feel that that community is transformative. It's absolutely essential.

Well, thank you so much. It's been a great pleasure for me and really interesting. I've been fortunate enough to be able to interview a few of you who have Type 1 or involved with Type 1 and it's been very interesting and an education for me and hopefully will be for the listeners as well. So thank you so much. It's been a great pleasure.

Thanks for taking an interest in people with Type 1. It's important to us and thank you to all your listeners for being interested also.