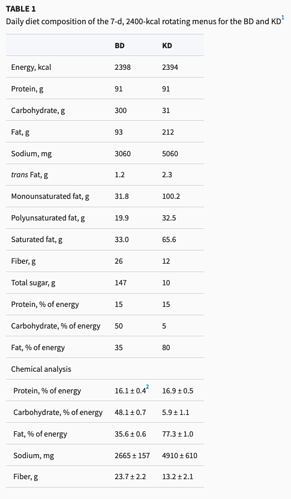

@OldDoug Following is the food content of Hall’s study, KD is the ketogenic version. I don’t think you can criticize this as not low enough for ketosis. It likely was for most if not all subjects. Read Eades’ comment on the study. According to Eades the real problem (for Hall) is that the study confirms keto rather than not.

A Calorie Is Still A Calorie - Why Keto Does Not Work 😖

Fung’s critique of Hall’s study. Like Eades, Fung suspects that the findings of the study didn’t support Hall’s wishful thinking so Hall just made up what he wanted.

You can if you want but those effects only apply on a carbohydrate diet. Something else happens when ketogenic but not in everyone who is ketogenic for various reasons.

What causes obesity isn’t directly insulin but the indirect “search” for blissfulness. The more someone eats carbs… the more their serotonin and probably other neurochemicals rise but never enough to make them feel blissful. Then not eating carbs will lead to a drop in Serotonin. Vicious cycle of addiction. Insulin is just a bystander.

Okay, yeah, makes sense. I wasn’t referring to Hall’s study but rather a generalized view of purported “low-carb” studies, which sometimes means “only” 15% or 25% or even 40+% carbs.

So, 7 day rotating menus? That sounds brutally insufficiently short, to start with. Again, not specifically about Hall’s study, since I don’t know the details offhand, but somewhere in this thread is a mention of studying people where they ate varying diets for 4 weeks, then an equalization or ‘washout’ period, and then 4 weeks of another diet (high or ‘low-carb’) it was claimed. But even 4 weeks really is not enough to give true low-carb a fair trial, i.e. fat-adaption alone can take longer than that.

@OldDoug I agree that most studies that find ‘ketogenic diets don’t work’ are either of too short duration and/or too high carb meals that are portrayed as ‘low carb’ or ‘ketogenic’ when not. I suspect that if Hall’s study had been longer it would have shown even greater fat loss than it did. But even at only 4 weeks, it showed fairly conclusively that the KD diet works. Both Eades and Fung in their independent analyses agreed the data showed a positive result from KD. Both also agreed that the data not only showed a positive KD outcome, but so positive an outcome that Hall had to spin the results with bafflegab to try to make it look bad.

One issue that Eades discusses is the metabolic chamber in Hall’s study:

But immediately Hall tells us there was something wrong with using the metabolic chamber. As Hall says, much to their surprise, they found out that the energy expenditure of subjects in the chamber is unnaturally low. So when the researchers fed the subjects the number of calories they thought they needed as revealed by the metabolic chamber they were dramatically underfeeding them. There was quite a discrepancy. Says Hall:

One of the interesting things was that despite the fact that we were trying to put them in energy balance in the chamber and we were actually able to do that. Um, outside the chamber they actually burned more calories. Not too surprising in retrospect but we actually were surprised by the magnitude of how many more calories they were burning outside the chambers. Upwards of 500 calories a day more outside of the chamber than inside the chamber. So what that meant was that we were feeding them more or less in balance in the chamber but we were underfeeding them outside the chamber.

When Hall says, “not too surprising in retrospect,” he might as well be saying “oops!” And what he also means when he says that is his own colleague and last listed author on this study, Eric Ravussin, published this finding 25 years ago. This makes me wonder why they didn’t plan for it in advance.

Here’s the full text (pdf) of the study that Hall and Ravussin published 25 years ago that Eades finds interesting. Here’s a more recent paper discussing the same phenomenon, ie subjects expend much more energy on the metabolic ward than in the chamber.

In Hall’s study, the people consumed from 31.1 to 40.5 grams per day for the ‘ketogenic diet’ phase. Insulin did decline, and ketones increased by a factor of ~7. For Beta–hydroxybutyrate, the average level was 0.758 mmol/L, so not far into ketosis at all, really just toward the lower end of “nutritional ketosis.”

This does seem to be the case, and to what extent could Hall’s study truly “debunk the carb-insulin hypothesis”? The write-up of the study begins with this sentence:

The carbohydrate–insulin model of obesity posits that habitual consumption of a high-carbohydrate diet sequesters fat within adipose tissue because of hyperinsulinemia and results in adaptive suppression of energy expenditure.

(Just on its own, that doesn’t seem quite right to me. High-carbs; fat storage because of high insulin = all good so far. But to say that “results in adaptive suppression of energy expenditure”? I don’t see it as a necessary “adaptation,” but rather a different description of the same thing. Energy being stored as fat means that it’s not available for metabolization, for expenditure.

So by definition at that point there is less available energy for expenditure; considering the energy balance demands acknowledging that. Thus it’s not that the body “decides to expend less energy,” i.e. adapts in that way, it’s that it has no choice.)

More importantly, I think, the carbohydrate–insulin model (CHO) doesn’t claim that everybody who eats high-carb will suffer the same metabolic fate. CHO says it can happen. It does happen for many people. But just because a given group of people don’t display a marked difference when on different diets does not mean that CHO isn’t valid for others.

Nor that advantage for low-carb would not become more apparent under different conditions and/or longer time periods. The study participants were said to be “overweight or obese,” so I’d assume there was some insulin resistance there, but it’s a question as to how much.

Low-carb resulted in “Daily insulin secretion, as estimated by 24-h urinary C-peptide excretion, rapidly and persistently decreased by 47%…” It would be nice to know what the fasting insulin levels were, at the beginning of the study and at intervals along the way. Insulin went down, as one would expect it would, but we’re left hanging as to just how insulin-resistant the subjects really were.

The test subjects were really not used to ‘eating keto.’ People whose habitual diets got less than 30% of calories from carbs were rejected. 4 weeks on ‘low-carb’ is not long enough to get an accurate picture. If they aren’t fat-adapted, then energy expenditure will very likely be less, resulting in interpretations that CHO isn’t doing what it claims to do.

I’m thinking this could skew things. 4 weeks on baseline diet, then 4 weeks low-carb. If less water retention - as is common - resulted from the low-carb phase, then this would be a confounding factor (actually making CHO look better).

Yes, and thus ‘f’ (which as you say is mostly set by insulin levels) becomes exceedingly important.

Kevin Hall is no defense for the Tudor Bompa Institute, nor vice-versa.

Consider a person fasting for more than a day or two - long enough for glycogen to be essentially “used up,” as much as it can be. Things get fairly simple indeed then.

Does it actually get used up, or does the body start to make more from scavanged protein (autophagy and gluconeogenesis)? Do we even know?

This is a fascinating discussion. Thanks, all, for your thoughtful contributions.

It makes more. There’s still parts of the body that have to have glucose, so some of that is going around, and even with ultramarathoners and the like there’s still some glycogen that will be there (after exercise-induced depletion), though likely only a tiny bit. Just a guess - we know the body will be eventually very reluctant with fat as starvation progresses, it doesn’t want to give up that fat and risk truly having the tank run empty and dying. For glycogen I’m thinking of it like it’s exponential - it goes down but as it nears zero the rate of depletion also slows down a lot.

For people who fast, being on a very low-carb diet when eating means a slower rate of glycogen production. I assume it’s far less than on high-carb. I picture it like for extreme long-exercise athletes. Fasting means even less glycogen production, but over time the body gets used to that happening and compensates.

For that matter, I’m guessing it’s that way for high-carb diets too. First couple times fasting, maybe the body thinks it’s just a momentary hiccup in the food intake and that lots more carbs will soon be in the pipeline and it will be easy to replenish glycogen. But with a lot of time fasting, the body learns and adapts…?

I think, that 31g carbs is too high for the KD / ketosis diet, and furthermore, KD is way too high in the unhealthy polyunsaturated fats. 33% of the 31g of carbs are sugar; this also is a no-no. 91g of protein, if we allow 0.7g protein x LBM (lbs), then this diet, I suppose, is referencing a diet made for a person with a LBM of 130 lbs. If we use 0.8g protein per LBM, then the body LBM weight would be around 114 lbs.