I also think the differences with time restricted eating is even (stable timing) depletion and replenishment of glycogen storage and even (stable timing) oxidation of glucose and fatty acids?

My nutritional framework - Dr. Peter Attia

A Calorie is Not A Calorie - A Discussion of Thermodynamics

A Calorie is Not A Calorie - A Discussion of Thermodynamics

That matches my approach.

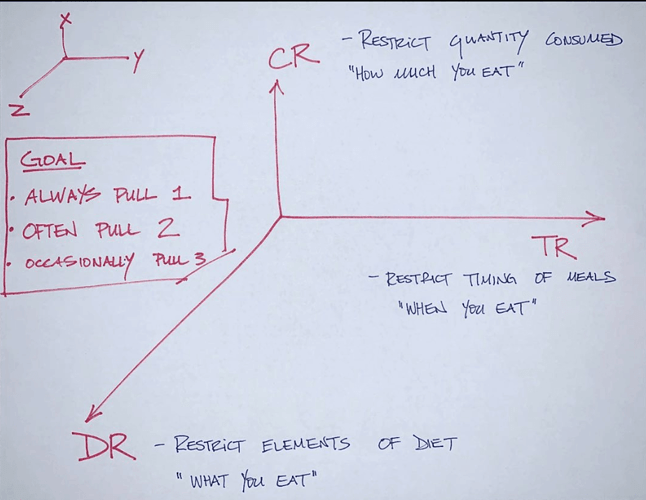

It also (for me) coincides with the stages of getting your eating into a good, healthy pattern. Stage 1 was managing what I was eating. Cutting out the bad stuff (sugars, starches, processed foods, artificial things). Stage two was managing the timing - cut out snacking, introducing occasional fasting. Stage 3 was managing overall quantity. Now that I was eating the right things, at the right times, focusing on portion sizes.

I also have a 4th axis - “What you do with the energy you eat”, i.e. adding activity and/or exercise into your day.

I suppose that has it’s own set of axes - what kind of exercise and activity, how much you do it, and the timing of it.

You say “for me”, but my hunch is that there’s some real behavioral science behind this. The same pattern has worked for me too:

-

first shift to eating keto,

-

then add in and ramp up intermittent fasting (easier when keto-adapted and not feeling the need to constantly spike blood sugar)

-

finally tweak portion sizes and overall quantity.

These steps can be interleaved in many cases, and it’s not always a simple progression. For example, lots of people return to the earlier stage of “what” if desired weight loss or body recomposition slows. In many cases they change to less liquid fat (no heavy cream, no MCT oil), fewer energy-dense foods like nuts and cheese, etc.

But it makes sense that a more “foundational” stage needs to be more or less on track before adding a new stage - it’s like habit formation.

The common failure of diets that focus primarily on calorie restriction (or “points”) also makes perfect sense: if you eat foods that make you want to eat more, and eat every two hours or less, it’s hard to go from there to time restriction or quantity restriction. The food itself is instructing your body to get more of it.

Fundamentally, this could be wrong. Nuts are bad because of PUFAs, which make you hungrier. However, other fats, like stearic acid, make you less hungry. I’ve been testing a much higher saturated fat diet, with success. It makes me less hungry.

Moreover, see this, where Siobhan Huggins ate a higher fat diet and lost weight:

I believe this is due to her being on a very low PUFA diet and eating more relative amounts of saturated fat, particularly stearic acid.

By the way, I’m not saying these theories are correct, until validated by RCTs. Even then, as a scientist, no theory is correct; it’s just a theory.

Inspired by your example and other discussion in this board, I’ve been experimenting with cocoa butter as well. I’ll take a little chunk (1-2 tbsp) and suck on it like a lozenge.

It tastes kind of like chocolate without the sweetness or the chocolate.

It’s a pleasantly creamy texture and taste though.

It’s a pleasantly creamy texture and taste though.

Well, in full disclosure, I went from reading Jimmy Moore’s Keto Clarity and adding fat to everything. But I wanted to prove Ted Naiman wrong, so I bought a CGM and ate tons of protein, with lower fat. Then, I decided I liked higher protein, lower fat, and that higher fat does not seem satiating. I also figured out that – for me – I could find no detriment to protein (no blood sugar swings, for instance).

Then, after reading up on the Protons theory from Hyperlipid, I thought maybe higher fat could be “good” again. And then when The Croissant Diet came out, I was floored. He created a great diet that addressed a lot of concerns I had.

And, if you’re in this (low carb) space long enough, you realize there’s a fight between people who believe sugar is Evil Incarnate, and others who believe sugar might not be bad, but PUFAs are Evil Incarnate.

And, as an engineer/scientist, I don’t think anything is “correct”. If I can be proven “wrong”, then that’s OK. It advances science. And I also know there are limits to N=1 testing, as sometimes I test something multiple times, and each time get a different result.

But if this theory is true, it opens up the possibility for someone like me with kids, that we could move to selective fats (reduced olive oil, nuts, avocados; more cream, butter) and have that reduce our kids’ appetites. I can tell you right now that exercise has nothing to do with weight, as one of my daughters has 6 hours of dance every week, yet gets heavier with carbs/PUFAs and lighter with no carbs/PUFAs. (They tend to go hand in hand, as anything “prepared” has PUFAs in it.)

So, I’m still testing higher saturated fat. I hope it works, as it’s easier for me to make high fat foods for my kids, and get them to like it. If I can give them rice with tons of butter, or croissants filled with butter, I can get them to eat easier than if I tell them they can only have meat and vegetables.

I was thinking about something much like this the other day. I suspect that how bad any given thing is for you is related to the overall calories content of your diet.

As in: say you’re eating 300 grams of carbs. I suspect that the effects on your body are going to depend (in part) on what the overall calorie load IS. If you’re eating 300 grams of carbs, and like 10 grams or protein and 10 grams of fat, well, I suspect (he said, overusing the word) that you’d have a different result in a low calorie diet than 300 grams of carbs with 200 grams of protein and 400 grams of fat.

Which, obviously, is an extreme example. And that’s not to say I think you SHOULD do those things, but it wraps around to the levers here - context matters. There’s likely different long term effects from eating a high carb (or high anything) diet where you ADF, even if calories are equal, than the same thing daily, and so.

So there’s a complex context.

And obviously, it’s not like the various levers are seperate. What you eat will very likely effect how much you eat, how you eat, etc.

Hmmm maybe if you have a vitamin B-6 deficiency or it’s not in the PUFA foods your eating?

If you didn’t get enough PUFAS, your skin falls apart, cracks (lips?), blisters, gets dry (e.g. eczema, dandruff, mysterious skin conditions?)…ect.

Seemingly the main or partial (co-factors; folate B-12 etc.) determinant of PUFA absorption is factored around B-6?

”…Vitamin B6 is a water - soluble vitamin. Water - soluble vitamins dissolve in water so the body cannot store them. Leftover amounts of the vitamin leave the body through the urine. Although the body maintains a small pool of water soluble vitamins, they have to be taken regularly. …” …More

ctviggen footnotes:

[2] Effects of vitamin B-6 on (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism.

[3] “…Overall, these findings suggest that vitamin B-6 restriction alters unsaturated fatty acid synthesis, particularly n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis. These results and observations of changes in human plasma fatty acid profiles caused by vitamin B-6 restriction suggest a mechanism by which vitamin B-6 inadequacy influences the cardiovascular risk. …” …More

[4] Possible Mechanisms: Why stearic acid does not raise blood cholesterol levels has been the subject of considerable research and several possible explanations have been proposed.2, 3, 17 Although early investigations in experimental animals suggested that the absorption of stearic acid is less efficient than that for other SFAs such as lauric, myristic, and palmitic acids, subsequent studies in humans have shown that the absorption of stearic acid (94%) is only slightly lower than that of other SFAs (97% to > 99%).2, 3, 26 Thus, reduced stearic acid absorption does not appear to explain differences in plasma lipid and lipoprotein responses to stearic acid compared to other saturated or unsaturated fatty acids. Another hypothesis is that stearic acid is rapidly converted in the body to the monounsaturated fatty acid, oleic acid, which does not affect blood cholesterol levels.2, 3 However, in humans this conversion appears to be limited, as approximately 9% to 14% of dietary stearic acid is converted to oleic acid.2, 27 An alternative hypothesis to explain stearic acid’s neutral effect on blood LDL cholesterol is that stearic acid, unlike hypercholesterolemic SFAs, does not suppress LDL- receptor activity in the presence of dietary cholesterol.2 Another possible explanation is that dietary stearic acid reduces cholesterol absorption, perhaps by altering the synthesis of bile acids and consequently the solubility of cholesterol. Although this effect of stearic acid on cholesterol absorption has been shown in laboratory animals, it has yet to be demonstrated in humans. Clearly, the question of what biological mechanism(s) underlies stearic acid’s regulation of cholesterol metabolism remains to be resolved. …” …More

[5] Dietary stearic acid regulates mitochondria in vivo in humans

Update:

Intermittent Fasting:

Metabolic switching and different forms of fasting.

In my previous email, I laid out a nutritional framework, consisting of 3 levers—dietary restriction (DR), caloric restriction (CR), and time restriction (TR)—and alluded to a recent review in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) highlighting TR (i.e., when you eat and don’t eat).

(We also just released an AMA exclusively on fasting.)

A staple of the NEJM is research relating to treatments for disease, and how they can be used in the clinic. The review article from the NEJM—“Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease”—is no exception. After describing the potential mechanisms underlying its beneficial effects—metabolic switching and stress resistance chiefly among them—the authors go on to describe the reported effects of so-called intermittent fasting (IF) on health and disease, and finish with recommendations for how health care providers can help their patients implement this eating pattern to treat or prevent a number of metabolic maladies.

(I say “so-called” IF because I think this term is confusing and inaccurate. The authors conflate three distinct forms of fasting into one in their definition of IF: Alternate-day fasting (ADF), 5:2 intermittent fasting (5:2), and daily time-restricted feeding (TRF). This is confusing because these are quite different forms of fasting or restriction. It’s important to distinguish between them. The other problem within these definitions is the flexibility around the term “fasting.” Most studies on ADF and 5:2 allow up to 700 Calories per day on fasting days, while others don’t allow any Calories. I’m very particular about the definitions because I think different forms of fasting and restriction may have different physiologic effects, and I worry that by lumping all forms together, we may dilute such insights.)

One of the aforementioned mechanisms, metabolic switching, refers to the preferential shift from the use of glucose as a fuel source to the use of fatty acids and ketone bodies. Your ability to toggle back and forth between these two metabolic states is an indicator of your metabolic flexibility. For those interested, I’ve discussed this concept in more detail on the website (here and here) and most recently with Iñigo San Millán on the podcast.

The authors question how much of the benefit of IF is due to metabolic switching and how much is due to weight loss, which often, but not always, accompanies fasting. They point out that many studies have indicated the benefits of IF are independent of its effects on weight loss. They also emphasize that ketone bodies produced from fasting are not only used for fuel, but are also signaling molecules that have profound effects on metabolism and are known to influence health and aging.

What is the level of ketosis one must reach in order to elicit these benefits? The minimum threshold appears to be about 1 mM, at least in mice. This raises the question of whether different types of fasting achieves levels above this threshold. According to the authors, plasma ketones generally increase to 0.2-0.5 mM during the first 24 hours of fasting.*

*In the review article, the authors wrote, “In the fed state, blood levels of ketone bodies are low, and in humans, they rise within 8 to 12 hours after the onset of fasting, reaching levels as high as 2 to 5 mM by 24 hours.” We wrote to the corresponding author questioning this and he confirmed this was an error in the paper and he’s submitting the change to the editor.

Given the importance put on ketone bodies by the authors, it’s surprising that very few trials in humans measure plasma ketones during IF, TRF, or ADF. But if it takes 24 hours for ketones to reach up to 0.5 mM, and the beneficial threshold is 1 mM, it suggests there may be a dosing problem with some forms of fasting. This raises the possibility that the metabolic switch isn’t occurring in some types of TR.

In one trial that did look at morning ketones after 4 days of TRF (18-hour fasting window) in 11 overweight adults, levels were 0.15 mM. In a different trial, a one-week 5:2 IF regimen in 19 healthy female participants, in the morning after the full (and non-consecutive) days of fasting (about 36 hours of fasting), self-measured BHB levels were 2.58 and 1.14 mM, respectively.

However, these studies are very small and lasted a week or less. Whether the results are reproducible and what happens when people engage in these regimens long-term hasn’t been determined. Do people improve their metabolic flexibility during long-term TRF, IF, and ADF? Do the levels, and utilization of, ketones increase over time? Does one regimen work better than the others in this regard? Does a ketogenic diet mimic the effects of TR (or does TR mimic the effects of a ketogenic diet)? If we have any chance of sorting this out, we need to start carrying out more (and longer) studies that look at different forms of restriction and measure the thing that presumably matters, in this case, ketones. …” …More

Tried NOT counting calories and scale went UP

Fasting energy limits and body composition mystery