Originally published at: https://ketowomanpodcast.com/belinda-lennerz-transcript/

This transcript is brought to you thanks to the hard work of Karen Jones.

Welcome Belinda to the Keto woman podcast. How are you doing today?

Thank you. Yeah, I'm doing very well

Enjoying the conference?

It's a wonderful conference. I've had a great opportunity to meet a lot of very interesting people here.

It's really good, isn't it? And I've, I've noticed there are lots of people involved in the Type 1 community here.

Yes. I was excited to meet many people I'd heard of in the discussion group yesterday and to have the opportunity to exchange ideas and it was wonderful.

Fantastic. Well perhaps you could tell us a bit about you.

I'm in pediatric endocrinology at Boston Children's Hospital and I've taken care of people, and children especially, with Type 1 Diabetes for several years now and worked mostly in obesity research. And we have recently come across a Facebook group called Type 1 Grit that are following a very low carbohydrate approach for Type 1 diabetes. According to a book by Doctor Bernstein called Doctor Bernstein Diabetes Solution. And I was just blown away by the success they have in managing their diabetes as it compares to my experience that I have my own practice and in seeing children with diabetes at diabetes camp who eat a standard diet with a high amount of carbohydrate. And so that got us into wanting to study this approach and into wanting to learn more about it to see if we could bring that to our patients as well.

Yes, because really logically it seems like such a good approach when you're trying to manage blood glucose levels all the time. So it just seems the easiest way, to eat this way to keep your blood glucose within a certain range. Logically to me that that just seems that it's going to be the easiest way to manage your insulin.

Logically, it does make a lot of sense, right? And in fact, before insulin was discovered, that's how diabetes was managed. And then when insulin came about, carbohydrate restrictions were just loosened gradually over the years to the point where now we recommend a fairly high carbohydrate diet for people with Type 1 diabetes. And surprisingly, I don't think that anyone has really done the studies to show that that's the way to go. So I'm really looking forward to hopefully contribute a bit to that.

Yeah, exactly. So tell us a bit about the study you've been doing.

So this study, this is really a first effort to look at what people are doing and to describe their success. So what we did for this as studies, we just posted a fairly simple online survey to the Type 1 Grit community. At the time of the survey there was about a thousand people following the low carb diet recommended by doctor Bernstein. Now it's over 3000 the last time I checked yesterday.

And so we ask people, you know, what do you do? Like, what's your typical diet, how much carbohydrate do you eat, what's your hemoglobin A1c? We ask them to download some of their meter reads, look at their day to day variations in blood glucose levels. We ask for complication rates because a lot of people are worried that low carbohydrate diets may increase risk for ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia, poor growth, etc.

So we did ask about those things as well. I think what's special about our study is that we actually also ask people for permission to talk to their medical doctors and providers so that we could get some objective information from those people as well to validate what participants had reported. Because one of the largest concerns with surveys is that you never know what people report or recall correlates with what's actually happening. And so having information from two independent sources really increases the confidence in your findings.

We were able to survey over 300 adults and parents of children with Type 1 diabetes and found remarkable glycemic control in that group with an average hemoglobin A1c of 5.67%. And that is really something that's thought impossible to achieve for people with Type 1 diabetes. Because if you want to control your blood sugar to a certain degree, at some point you're going to risk having too low of a blood sugar. Because what, especially when you eat carbohydrates, your blood sugar goes up and down a lot, right? Every time you eat carbohydrate and cover it with insulin, you will inevitably see a peak followed by a drop in blood sugar. So if you, as you're trying to bring that peak down, you're going to risk or have a low sugar reading later. And of course that has to be prevented almost at all costs because that kid cause coma, a seizure, a severe problems down the road.

That seems to be the biggest fear in the community of the Hypo.

That's a huge, you know, because it's a huge immediate threat, right? And people experience that, you know, some people have lows every week or every day and so you know, you constantly have to mitigate how low can you go without being in trouble?

And is it true that the, again, my logic, the higher peaks, the lower and the more potential you're going to have to dip into that hypo zone or does it not necessarily work that way?

Well, it's likely because a lot of the highs and the lows result from a mismatch between insulin action and carbohydrate uptake. And the larger that dose of insulin that you take, the higher the risk for a big mismatch, right? If you eat a very small amount of carbohydrate and you take a small dose of insulin, you might have a mismatch, but it's not gonna be as massive as if you ate 10 or 40 times more carbohydrate and you would have taken 10 or 40 times more insulin for that.

Absolutely. How long was this study? The participants, how long were they reporting?

So this was just an observational study so it was a survey that was posted at one time point. And so we had asked people to report on their experience. So the study itself has cross sectionals, but we had people reporting being on the diet anywhere between three months and 60 years.

Wow. Really?

Yeah. Average time on the diet was right around three years. Most people between maybe two and five years.

So I'd be really interested to hear some of the details with those people who had been on it for such a long time.

Right. At this point we just asked everyone the same questions, so I don't have a way to know much specific about the people who've been on it for a long time. But we do hope to do some followup work. I actually just got funding for a randomized controlled trial for a very low carbohydrate diet for people with Type 1 diabetes compared to a standard diet where we're going to deliver meals to them and then measure their blood sugar control in our research unit, have them on continuous glucose monitors so we can track their readings very closely.

And so in order to make this a meaningful intervention, I plan to reach back out to some people off the Type 1 Grit community and other people who are following low carb. So I think in that setting, I'll be able to tease out more details about what do they really do on a day to day basis, what's their diet, what's their macros, do they eat plant based or animal base. You know, all those questions are fascinating and unanswered yet.

And so what was the scope of the study and the questions you were asking? And so the results, the feedback you got.

When we heard about this group, you know, first of all that was a phenomenon like achieving such good glycemic control that's unheard of in people with diabetes. So really our first point was setting out to make sure they actually had Type 1 diabetes and not maybe Modi or Type 2. So we had a lot of questions to ask for diabetes antibodies and age at diagnosis and those kind of things and it really appears that almost all people who participated in the survey do have Type 1 diabetes.

And then we wanted to know their overall blood sugar control, which was very, as I said. We had asked for hospitalizations and hypoglycemia rates, ketosis rates, use of Glucagon. And so all of those possible complications that people think maybe associated with a low carb diet, they were very low in this group when you compare it to other studies that survey people with diabetes and who follow standard protocols. There were low rates for Ketoacidosis, low rates for diabetes hospitalizations, low rates for hypoglycemia.

We had looked at growth in children or height I should say, because if you want to look at growth, that's difficult, right? You have to look over a period of time. And because this was just a single time point, we could only look at height and we had asked some of the physicians to provide growth data from when they're diagnosed. So a subset of kids, we actually have growth rates over over a two year period and about 30 to 40 kids. And they appear to have grown normally as far as I can say. And then everyone was above average or even above average tall. So we didn't see any impacts on growth even though that would not be the right study to perfectly answer that question.

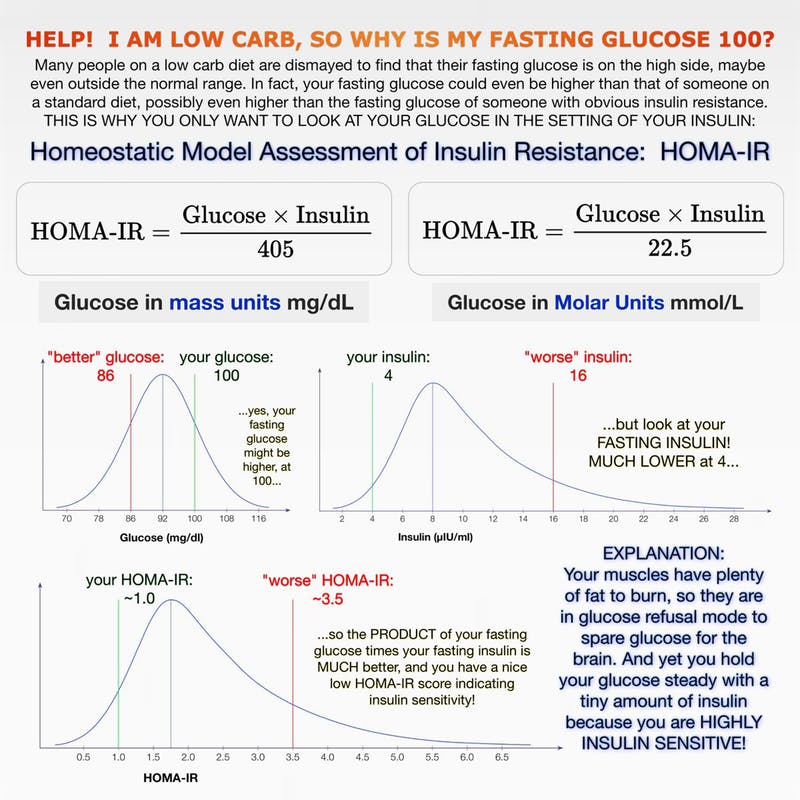

We found that people have a very satisfied with their diabetes control and strategies. They were less satisfied with the medical care that they received. And that was a big concern that study raised for me because at least 30% had said they didn't feel comfortable sharing with their diabetes care provider that they were on this diet. And, even the people who felt comfortable sharing that, a large proportion of them felt like the physician wasn't supportive and wasn't helpful in managing their diabetes in that setting. And so that made me as a physician very uncomfortable because I think that an honest relationship between physician and patient is paramount, especially if it comes to something so physiologically influential as a diet because you have to have a whole different set of considerations - as we heard at the conference, your lab tests will look different; you may have different risks for complications; and when you get sick, you may need different management advice - you may not be managed the same as someone who's eating a high carb diet.

So I felt that was a very sad finding to see that those people who are so tremendously successful and dedicated are so unsupported or feel so unsupported. And I think there was a real lack of information about this approach and it is very important to do more research, to educate the medical community and to help enhance and make resources available so that there could be better communication hopefully.

Yeah. Because the potential feedback for the advantage of the physicians, I can see so much potential there as well. It's not just the patient thats missing out, but it's their physician that's missing out gaining valuable knowledge for perhaps a potentially better way to manage this problem.

I think it's a mess all around because diabetes, Type 1 Diabetes especially, is an incredibly challenging, dangerous disease to manage, it's very high risk, it's a lot of work. You really need a team, you should be working together. Y you shouldn't have to start out trying to do this on your own.

No, and that just heightens the fear and anxiety that's so closely bound with having the condition, I imagine. And perhaps you could talk a little bit about Ketoacidosis in this situation and the potential concern. Whenever anyone starts talking about ketones in the community as a whole, there's a real misunderstanding between being in Ketosis and Ketoacidosis - it's cited as you shouldn't do Keto because of this. And most of us are well schooled in the fact that for the majority of people, it's not an issue unless you're a Type 1 Diabetic. And so I can imagine that for people potentially using this way of eating to help manage their Type 1, that must be a red flag that comes up, that is going to be something that they're concerned about happening.

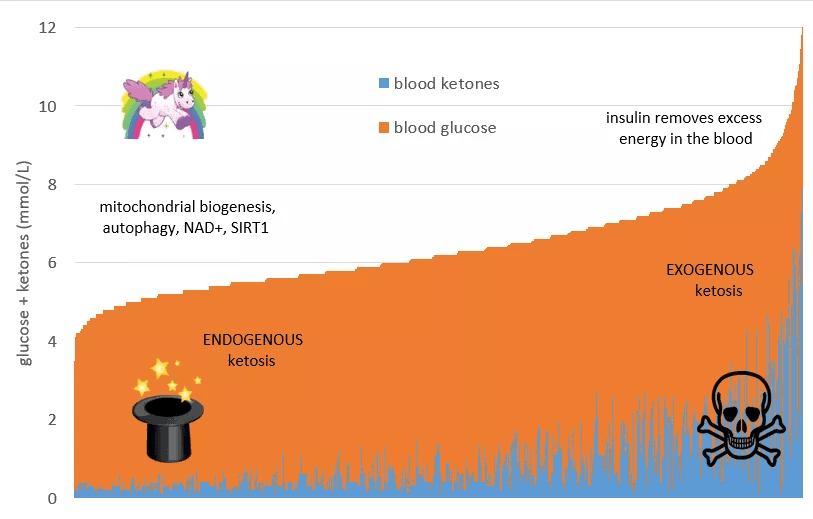

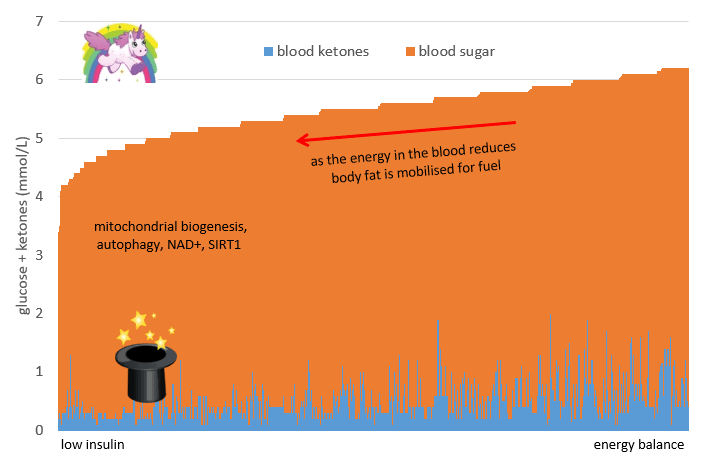

Yes. I'll start by saying that there is really no research and no literature to actually know the right answer in this and that's what makes it scary. The concern with eating a very low carbohydrate diet is that most likely, depending on how low you go, you might be in nutritional ketosis, and in fact, I know that some people specifically aim to be in nutritional ketosis to have health benefits.

As we've heard at this conference, if you don't have Type 1 Diabetes, if you have Type 2 Diabetes or if you don't have diabetes at all, your ketone levels almost cannot exceed a certain level because if your ketone levels rise to an unsafe threshold, your body will actually make insulin triggered by the ketones themselves to bring them back down, so it's a calibrated system. It's stable.

If you have Type 1 Diabetes, you do not have that opportunity, so if your ketones could go incredibly high without your body having the ability to intervene because you cannot make insulin. And so that's why people with Type 1 Diabetes, no matter what diet they're on, they're at risk for having ketoacidosis if they don't get sufficient insulin by injection or by insulin pump. So that's always a risk.

When people who eat a standard carbohydrate diet, when their insulin delivery is interrupted or when they get sick and become so insulin resistant that whatever insulin they get doesn't work, the first thing you see is their blood sugar will go very high and then you'll know to check for ketones and then you'll know that you're in Ketoacidosis, and you could usually, if you're vigilant, you could treat it before it becomes real dangerous, so it's preventable.

If you eat a low carb diet, your insulin delivery may be interrupted or you may be insulin resistant from an illness and your blood sugar may still not rise very quickly because you don't have any carbs on board, right? You don't have carbs in your gut and you could still have a very low blood sugar event in the setting of insulin deficiency and you may go into ketosis or ketoacidosis even without having the typical warning signs of it, and I think that that's one of the concerns people have.

I've heard people be worried about potentially even having a lower threshold for ketoacidosis because your ketones are already elevated and you're kind of closer to it, again, there isn't really any good studies to support this. I wanted to point out that even though the Type 1 Grit community showed that they really didn't have a lot of Ketoacidosis, hospitalizations, or ED (emergency department) visits or episodes at all, this is a special group - they are very highly motivated, vigilant, incredibly engaged people that are very in tune with their diabetes care.

There might be other people who don't pay as much attention for whom I think the risk is probably substantially larger than this group that I had the opportunity to work with. I think what I want to say, in my opinion, again, without having a lot of research behind it, it's probably important to measure your ketones, especially if you're on a low carb diet to know what your baseline level is, and if you see deviation, if you feel sick or if you feel unwell to check it then and if you see any increase from what you usually run to be careful and to know that you could be at risk for having ketoacidosis.

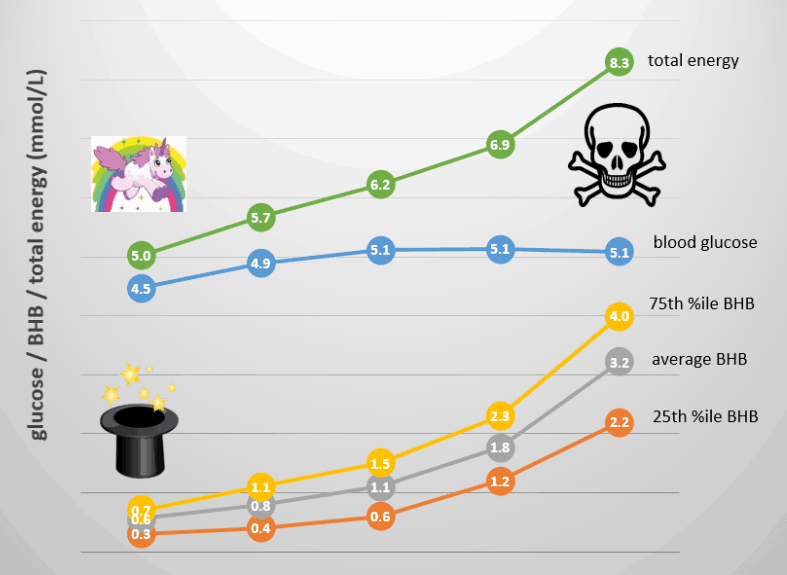

Yes, I think Cushner mentioned that yesterday. He was showing us the difference, with the constant glucose monitor, the difference in the graphs just in general between people eating the standard diet and a Keto or low carb diet, and that variance was incredible. But he mentioned about a particular time of risk, if something like an insulin pump problem or something happened during the night and you weren't aware of it and you woke up and maybe the ketones could be going up then. But then he spoke about that relative difference. Just as you said, knowing what your standard baseline is and what its increased to, it's more important - that difference between the two - than having a specific number that everyone should be concerned when their ketones get to that certain amount. It's very specific to you and what the differential is for you.

Right? Because I think there is a huge gray zone. For example, if you're on a high carb diet and your ketones are 1 and 1.5, that's not normal. So you at that point, you would want to start troubleshooting and looking for problems with your equipment or your insulin or to see if you're sick. You may want to take extra insulin to cover for that because that's not normal on a standard diet.

If you're on a low carb diet, you may habitually be at 1.5 you may even be at 2 or 3, depending on your constitution and what you do on your diet. But then going from maybe 2 to 3, that could be a warning sign, right?. We know that when you're at 10 you're in trouble. But when you were at 4 or 5, could that still be diet, could that already be Ketoacidosis? And the truth is you don't want to go to 10 before you intervene because that's when you're really in fairly severe ketoacidosis.

I think the key about ketoacidosis and successfully treating it is to catch it early. And so the early warning signs may be subtle. If your ketone levels are always elevated and knowing your levels will help you recognize a small increase and may help you treat early if you if you have to, because that's when you can still get a handle on it at home and be fine in a few hours versus having to go to the hospital and putting yourself at risk.

Yes. Again, it's this empowerment of the self knowledge and the knowledge of the environment in which you're working in. And again, the slightly sad aspect is if you have this mismatch with your medical team, because again, it's another example of where it's so important to be working closely with them.

Right. I know Jack Kushner, and myself certainly as well, we were trying to help inform the medical community about this approach, and also specifically help to provide research that may support a meaningful way to handle this.

And I know you did a presentation last night here at the conference, a special presentation, probably predominantly for Type 1s, but I know there were other people there as well. Was there anything you know of particular interest that came up in the Q&A that you'd like to share?

You know, I think it's, it's a lot of the same questions. People are very interested about the ketoacidosis question. I get a lot of questions about hypoglycemia, and specifically asking is is actually safe to be hypoglycemic when you're on a ketogenic diet? I think there is a notion that if you have high enough ketone levels and your brain can run on ketones, maybe it's not as dangerous to be in hypoglycemia and maybe you'd be relatively protected.

People say that they don't feel the lows as much, that they feel fine, they're fully functional. Why should I worry, right? I think again, that's a little bit of a dangerous territory because even if you feel fine, you're incredibly close to a threshold where you may not be fine. And to be truthful, there isn't any study or there isn't a lot of data to show you that you'd be fine solely on ketones, there are a few experiments, there are some animal studies.

And we're not going to be able to study that either because you can't really deplete someone in an experimental setting to the point where you could show, yes, I'm totally safe and fine without it, right? And who would want to risk their own brain? The brain is very vulnerable, it needs fuel and has no stories, right? If it's not fueled properly, you could have a seizure, you could go into coma, you could have brain damage. And I do think that ketones are protective to a degree, and I do think that the brain can use them as a fuel, but do you really want to press your limits to test that? I think that maybe not.

I guess that's where the anecdotal feedback really becomes important. So if people have got the data from their monitors and they can also feedback, well this is where relatively speaking I was quite low and that might be something that would affect somebody differently who was on a standard diet to me. And they can just feedback where you were saying that potentially some people were saying that they felt maybe they didn't experience hypos in the same way. So I suppose that's where the only thing that you say because you can't test it, is to just collect that anecdotal evidence.

And I also think that that's a double sided sword (is that what you say in English?). Because you're low and don't feel it, people think, okay, I can be low, I'm safe. But if you're low and you don't feel it, that's also a genuinely unsafe situation because feeling a low as a warning sign that helps you intervene. So if you're losing that warning sign, you could potentially go a while without knowing, and you could go severely, really low without having a proper warning.

If someone who eats a standard carb diet and who generally runs high, they'd feel terrible when they have a 70. At 70 you're miles away from a dangerous zone so you have a lot of time and you get a lot of warning to intervene. If you feel fine at 50 or even 40 even as I've heard from some people, you're really close to a zone where it may be potentially a little more dangerous and that we don't know enough about. I can't dismiss a hypoglycemia just because you don't feel it, because the feeling is also a warning sign.

How much feedback did you have? Was it part of the study with how people were feeling? How much improvement they were seeing from switching to this way of eating in their general wellbeing and lifestyle? I know it's something that can really impact that day to day living and cause a lot of anxiety. And the potential of a way of eating to diminish that and really improve your overall wellbeing seems like probably the biggest benefit, in a way, to just being able to live a "normal life".

So we had asked questions and had provided some scales to see how do you feel, how is your general health? And we'd also ask some open ended question, what would you like to tell us about this approach, and we got very positive responses. People reported that they're feeling great, that they had been able to put aside a lot of their concerns about diabetes and about highs and lows, that they feel that they're able to focus better and that they are just healthier because they don't have to go through those ups and downs, that it takes a lot of anxiety, especially off the parents' backs.

A piece of caution though is that obviously these are people who've adapted this approach successfully and who are enthusiastically behind it. So you will get the positive answers, right? If a person had tried it and had hated it or had been miserable or had maybe even been noncommittal, they would probably have not continued on this approach and they would not have ended up in this study.

So there is that bias inherent, right?

So there is inherent bias to this, but you know, those people who are successfully doing it love it.

Fantastic. And how have you found this influences your practice?

I've been supportive of patients who've chosen to be low carb. I've tried to learn as much as possible as I can. Even before I did this study, I did read the book that Dr Bernstein had written and I actually went to visit with him for a week to learn from his practice. While I've been supportive, I don't feel like I'm in a position where I can teach people that approach yet.

I was going to ask you if it's something you're actually at the level where you recommend or whether you're just supportive of people who've decided to do it.

Again, I'm still being supportive and I'm still trying to explore structures. I haven't at this point met a dietician who can actively support it, I don't have a diabetes nurse educator that can actively support it. We're in the process of trying to build those structures because I'm intrigued, but I do think to offer actual teaching and education as a medical team, it's a high responsibility and I want to do it right. I don't want to do half finished things and then end up with patients who are not optimally cared for.

Absolutely. Yeah. Good. Good approach.

So we support it. If someone comes to me and says this is what I'm doing, I'm eager to help them and learn with them. But I haven't, I'm not yet offering it.

So people aren't finding that mismatch that we mentioned before,.

That's paramount, right? To keep the lines of communication open.

It kind of seems obvious to me but whatever approach your patient is taking, it's always going to be paramount to work closely with them to give them the best care you can. Yes. And you, you already mentioned there were some more studies that are going to follow on the back of this.

Yeah, I'm right now in the process of planning a randomized controlled trial, which is as you've heard a million times at this meeting, is considered the gold standard. It's really what we need to show ff this could be successfully brought to a wider audience, right? There is always going to be motivated people that can do certain things and that need to be supported. But my question as a physician, is there something that I can do to bring this to other people? And I feel like once I do that trial, I'll have learned a lot from my own practice and hopefully can provide information for other providers who might be interested in promoting this. So this is going to be a smaller trial, about 40 people, and if it's successful, the next step might be larger and maybe multicenter studies and hopefully informing diabetes care.

I usually ask my guests at this point, and I appreciate that I'm springing it on you, for a general top tip for our listeners.

I think "Keep an open mind and be supportive and try to work together as a team".

Perfect. And that certainly fits in with what you've been talking about. It's been a great pleasure talking to you today. Thank you so much and I wish you all the best for your future trials and studies and your practice.

Thank you.