Latest US Dietary guidelines: Nina Teicholz article

Butter Is Not Back: The Broken Promise on Saturated Fats

Despite months of pledges to “end the war on saturated fat,” the 10% cap in the updated US Dietary Guidelines will remain—creating a contradictory document.

NINA TEICHOLZ

JAN 6

Delayed for months, the highly anticipated new U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans will be released to the public tomorrow, followed by a large (invite-only) event at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on Thursday. As promised, the new guidelines are expected to be only about eight pages, far shorter than the 100+ tomes of previous administrations. The guidelines are also likely to include a lengthy appendix with scientific reviews to justify their changes.

The one widely touted reform was an “end to the war on saturated fat,” as both HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and FDA Commissioner Marty Makary have repeatedly pledged since taking office—including as recently as Nov 27th. This was a revolutionary proposal. The cap on saturated fats has been a bedrock piece of advice since the launch of this policy in 1980, and it is why so many Americans avoid red meat, drink skim milk, and opt to cook with seed oils over butter.

Yet I learned from two administration officials that saturated fats will not be liberated after all. The longstanding 10% of calories cap on these fats will remain.

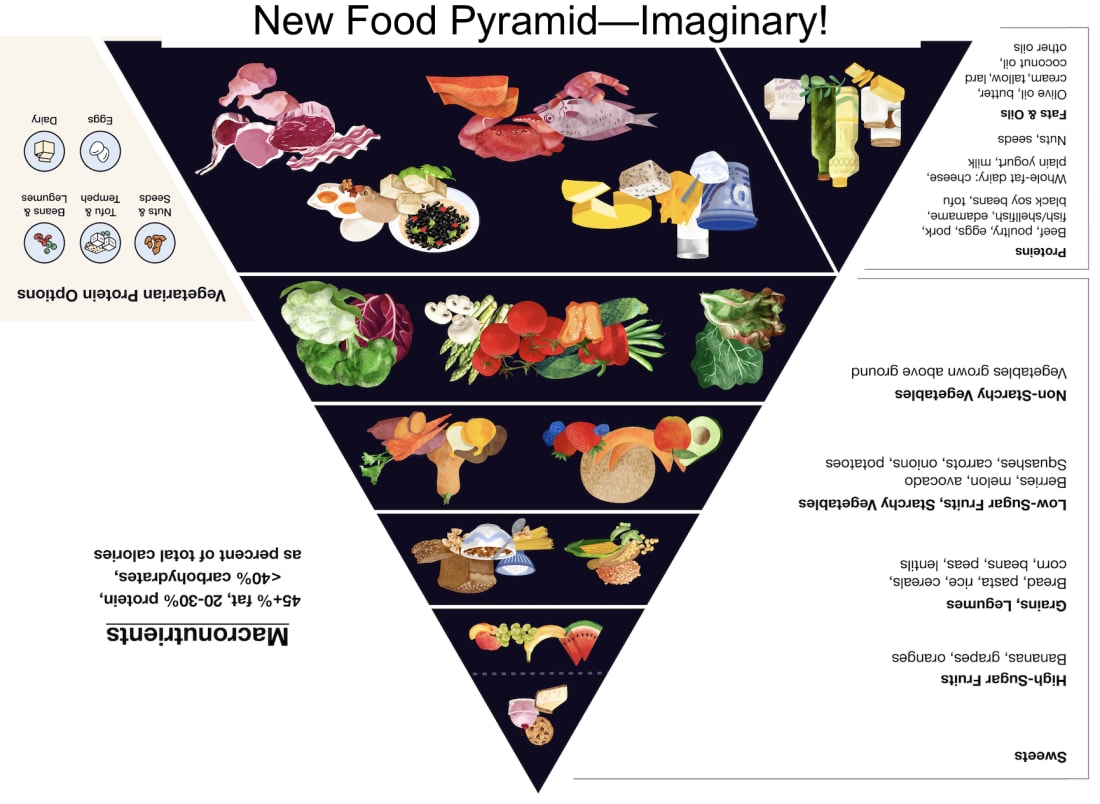

At the same time, the guidelines’ language will encourage cooking with “butter” and “tallow,” both of which are high in saturated fat. It will also introduce a colorful new food pyramid with proteins—including red meat—occupying the largest portion. These are powerful messages, never before conveyed by our national food policy, and are likely to influence consumer behavior.

Other Changes to the Guidelines

Before taking a deeper dive into saturated fats, here are some other details of the revamped guidelines I’ve learned:

• The limit on sugar will be dramatically lowered, from the current limit of 10% of calories to possibly 2% of calories, although that target may be for children only.

• A low-carbohydrate diet will be included as a possible option for people with obesity, diabetes, and perhaps other metabolic diseases. This is a huge win and one for which the Nutrition Coalition, the non-profit group I founded, has been advocating since 2020. This new low-carb option will be included in a section entitled “special considerations,” even though 93% of American adults are metabolically unhealthy, according to a 2022 paperbased on government data, making low-carb seem logical as a more mainstream approach. An important caveat here is that achieving a low-carbohydrate diet, which is almost always higher in fish, meat, dairy, butter, and fat generally, will be impossible with the continued 10% cap on saturated fats.

• A new food pyramid will be introduced. The original pyramid from 1992 (retired in 2005) had breads, cereals, and crackers at the base—altogether 7-11 servings of grains per day. This hefty load of grains has been widely criticized, especially since the current guidelines still require that half of those servings be refined grains. The new pyramid will replace that bottom slab of grains with proteins: meat, dairy, peas, legumes, and beans. Grains will be reduced to a smaller slab. I’m hearing only 2-4 servings per day—which would be a dramatic improvement.

• This new food pyramid will be upside down, in dramatic fashion, to show that this administration is ‘flipping the pyramid.’

A Contradictory Policy

Returning to saturated fats, the new guidelines will be contradictory. The general public will read about tallow and butter, see pictures of red meat amply illustrated in the pyramid, and may eat accordingly—ignoring the fine print about the 10% cap. For this audience, the guidelines may actually shift behavior toward more animal fats and nutrient-dense proteins.

But there’s another audience: the roughly 30 million children eating school lunches daily, plus military personnel, and the vulnerable populations—elderly and poor Americans—who receive food through federal programs, roughly 1 in 4 Americans each week. These programs are required by law to follow the Dietary Guidelines. For them, the numerical cap will trump any contrary language about butter and tallow. Cafeteria managers and program administrators will continue to adhere to the 10% limit, because that’s what the law requires.

For these captive populations, seed oils will remain the mandated cooking fat. The encouraging words about butter and tallow will essentially be meaningless.

Impossible to Reconcile

Here’s the fundamental problem: how can anyone eat butter, tallow, and red meat while adhering to the 10% cap? They can’t. The messages are impossible to reconcile.

The 10% cap means approximately 20-22 grams of saturated fat daily for the average 2,000-calorie diet. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

• 1 cup whole-fat yogurt for breakfast: ~5 grams

• 1 chicken thigh with skin, cooked in 1 tablespoon butter for dinner: ~12 grams

Total: ~17 grams of saturated fat

That’s nearly your entire day’s allowance in just two modest meals—no cheese, no butter on your vegetables. Add a splash of cream in your coffee and you’re over the limit.

Or consider another day:

• 2 eggs cooked in 1 tablespoon of butter: ~13 grams

• 4 oz ribeye steak: ~6 grams

• Broccoli with 1 tablespoon butter: ~7 grams

Total: ~26 grams of saturated fat

Already over the limit—and you’ve only eaten two meals. Anyone actually following the 10% cap will need to continue cooking with seed oils while limiting whole milk, cheese, and red meat.

Butter is not back. Steak is not back. Tallow will not be on the menu anytime soon—at least not for anyone trying to follow federal nutrition advice.

The Protein Paradox

I’ve also learned that the new guidelines will increase the recommended amount of protein from the current RDA minimum of about 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight to 1.2-1.5 grams. This is genuinely good news. Studies show this higher range is far better for weight loss, muscle maintenance, recovery from serious illness, and overall well-being—especially for school-aged children and older adults, two populations whose protein needs have been chronically underserved by current recommendations.

But here’s the paradox: with the cap on saturated fats still in place, this increased protein cannot realistically come from animal sources. A 4-ounce serving of lean beef provides 24 grams of protein but also delivers about 6 grams of saturated fat. Meeting the higher protein targets through beef, pork, or chicken thighs with skin would blow through the saturated fat limit by lunchtime.

So where will this protein come from? The only options that fit within the 10% saturated fat cap are peas, beans, and lentils—plant proteins that are mostly incomplete (lacking at least one of the nine essential amino acids), harder for the body to absorb, and packed with starch. To match the protein in 4 ounces of beef, you’d need over 6 tablespoons of peanut butter—between 500 and 600 calories, compared to 155 for the beef.

Paradoxically, this is exactly what the Biden administration’s expert committee wanted: more peas, beans, and lentils replacing animal proteins. More plant-based foods has been a progressive agenda item for years. Kennedy, who has publicly described his own diet as “mostly carnivore,” is thus fulfilling the exact report he pledged to reject.

This creates yet another contradiction. The new food pyramid will feature animal proteins—visually suggesting Americans should eat more meat and dairy. But given the saturated fat cap, that slab should really be filled with peas, beans, and lentils. The image will say one thing; the math will require another.

Why the Reversal on Saturated Fats?

I expect the typical response to the continued 10% cap on saturated fats will be that the competing science was insufficient to dislodge it. These views ignore the fact that there are now just as many review papers exonerating these fats as there are condemning them and that no review of the most rigorous data (from clinical trials) has ever found saturated fats have an effect on cardiovascular or total mortality (the most reliable health outcome measures). Scientific opinion has shifted steadily in favor of saturated fats over the past fifteen years—but that view has not managed to pierce through the guarded establishment consensus laid down 80 years ago.

What’s surprising is that Kennedy vowed to fight exactly that kind of entrenched “groupthink.” He and Makary not only repeatedly committed themselves publicly to reversing that thinking but were empowered by HHS, as lead agency on this edition of the Dietary Guidelines, having exceptional power. Leadership of the guidelines oscillates every five years between HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. (The White House, as I’ve come to learn, is also deeply involved.) HHS’s leadership position should have given Kennedy’s team the leverage to see his intended reform through.

What happened? A top advisor to Kennedy offered me several explanations. First, they didn’t want saturated fat to be the headline of the guidelines release—that would have been all anyone talked about. Other wins—on sugar and grains—would have been overshadowed. This is a legitimate concern, yet still highly disappointing given the disproportionate impact that liberating saturated fats would have had on American health. Allowing greater amounts of animal foods would have single-handedly resolved protein shortages and nutrient deficiencies (most of the essential nutrients lacking in the guidelines—iron, Vitamin D, and choline—are supplied in their most bioavailable forms from animal foods). Also, this reasoning is entirely political, not based on science.

Second, the advisor said they didn’t want the guidelines to be an “activist” document—a curious justification from an administration that has been fearless and activist on so many other issues. Why back down on saturated fats? The answer lies in a third rationale provided by this advisor: they felt they couldn’t be the only country in the world to change this advice, when all other national guidelines and the WHO maintain similar caps on saturated fat. Yet this amounts to following the herd rather than leading based on gold-standard science—Kennedy’s stated commitment.

I suspect deeper reasons are also at play. Although Kennedy’s top advisors have been eager to take on food companies like Kellogg’s and Nestle—corporate giants whose image makes them easy targets for public backlash—these same advisors appear far more reluctant to challenge the nutrition establishment: scientists at Harvard and the American Heart Association, institutions whose credibility with the media and medical community remains formidable. Taking on Froot Loops is one thing. Taking on anti-saturated-fats powerhouses Alice Lichtenstein of Tufts, Marion Nestle at New York University, and Harvard’s Walter Willett is another.

There’s also the matter of Kennedy’s base. His core supporters have come primarily from the world of anti-vaccine activists and others opposed to COVID-era interventions. On food policy, his coalition has no clear agenda beyond the need to eliminate food “toxins,” such as food dyes and other potentially harmful ingredients. Doctors and other experts involved in reversing obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic conditions—the very expert community that would have embraced liberating saturated fats as a means to resolving chronic diseases—have not been meaningfully included in the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) leadership. Without grassroots pressure, the political will to fight this battle was never strong.

Of course, industry groups would have been lobbying, too. The only industries pushing saturated fats, however, are dairy farmers—a fast-shrinking group—and the cattlemen (and women). My observation is that meat lobbyists are generally tied up with other issues (currently: screwworm, reciprocal tariffs, and trade policy, to name just a few). The Dietary Guidelines’ policy on saturated fat has typically been low on their list of priorities.

Finally, there’s the problem of expertise. MAHA nutrition advocates included influencers and podcasters—people like “Food Babe” Vani Hari and influencer Gary Brecka—many of them personable and passionate but with no published academic record on nutrition. Unlike the experts who challenged vaccine policy—many PhDs and even a former Harvard professor—the voices arguing against the saturated fat consensus lacked institutional credibility. There was no expert class putting forward rigorous arguments about why these fats had been unfairly vilified. Social media influencers carry little weight with the scientists who would need to be convinced—or the reporters who would cover the story.

The Evidence That Never Mattered

What makes this retreat so frustrating is that the scientific case for changing the saturated fat recommendation was strong. The 10% cap was supported by “no data,” according to emails obtained via FOIA from Alice Lichtenstein, who served as vice-chair of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee in 2015. The large, rigorous clinical trials on saturated fats—on 60,000 to 80,000 people worldwide—could never demonstrate that reducing saturated fat lowered a person’s risk of death from heart disease or any other cause.

Since I laid out the arguments to exonerate saturated fats in The Big Fat Surprise more than a decade ago, nearly two dozen review papers by teams of scientists worldwide have reached similar conclusions: saturated fats do not affect cardiovascular or total mortality. These are the most reliable health outcomes derived from the most rigorous data—clinical trials. The latest of these reviews, published only weeks ago in the Annals of Internal Medicine , concluded that restricting saturated fats could not be shown to benefit people without established heart disease—the very population covered by the Dietary Guidelines.

Even an outside expert review commissioned by HHS—anticipated to be published alongside the guidelines on Thursday—concludes that saturated fats do not affect mortality. This review does not support a continuation of the 10% cap. The evidence for dropping it is strong. It simply didn’t matter.

Political Capital Unspent

The MAHA movement promised to challenge the nutritional establishment. On saturated fat—the single change they had most publicly committed to, the issue Kennedy seemed to care about personally—they have blinked.

I’m encouraged by a number of other, truly meaningful reforms to the guidelines: reductions in sugar and grains as well as the inclusion of a low-carbohydrate option are important steps forward. Yet these gains will be undermined by the continued 10% cap on saturated fats—the most crucial missed opportunity. For the food served in school cafeterias, military mess halls, and hospital trays across America, skinless chicken breast, peas, beans, and seed oils will remain the order of the day—tallow, butter, and beef nowhere to be found.

For those of us who hoped this administration would finally align federal nutrition policy with the scientific evidence, Thursday’s event will be a lesson in how difficult it is to move the bureaucratic machinery of dietary advice—even when your agency leads the process, and even when the evidence is on your side.

Darn, you beat me to it. I could only find it on Substack, though. I’m glad you found it elsewhere.

I hate that they are not dropping the limits on saturated fat. That is one of the worst ideas that is completely unsupported by evidence. And it has deleterious effects, as whole fat milk isn’t in US schools, but highly sugared, nonfat, chocolate milk is, etc.

Moreover, look into all the evidence for C:15 (pentadecanoic acid), which is an odd-chain saturated fatty acid and comes mainly from – you guessed it! – fat in dairy.

It makes no sense, as Ms. Teicholz points out, to keep the saturated fat limit.

I do like the imagined pyramid, though. I know, putting out a visual that doesn’t agree with the guidelines will just bring contradictory experts crawling out of the woodwork, but at least the people who don’t read will briefly have a nice picture to guide them.

Yeah the math doesn’t work but most people can’t get a lot of protein from legumes anyway (it would require a huge volume and that’s tricky for legumes, even for past me and I could eat). Even if one has a high energy or lowish protein need or a low-fat enough diet so the lowish protein content is fine, completing must be done (maybe vital gluten may work for some so it doesn’t mess with the protein/energy ratio, in the contrary) and not everyone feels great when eating legumes (and gluten) so often. To put it lightly. I am not very sensitive but I would hate the feeling. Surely very many people are the same.

If anyone is interested, the Hungarian guideline is still the old one, lots of crazy specific rules but no numbers about fat, saturated or not. Encouraging lower-fat options (I kinda get it, we eat too much fat for our carb intake and good luck to take carbs from people. not like it works so well with fat here), limit for red meat but one still can get higher saturated fat. Mostly animal protein source, mostly plants for the rest (and variety for protein), lower limit for nuts and as little added fat as possible. Butter isn’t even mentioned but it’s fat so yuck I suppose. If even low-fat cheese is encouraged (I don’t think that is a valid thing), butter can’t be warmly welcomed. Poor butter. Or not as it’s awesome and people eat it.

No numbers for protein just “20% on the plate” and do whatever you do with that. I can’t interpret such things. At least you have proper numbers for protein, that’s nice. And a great base to criticize the whole thing…

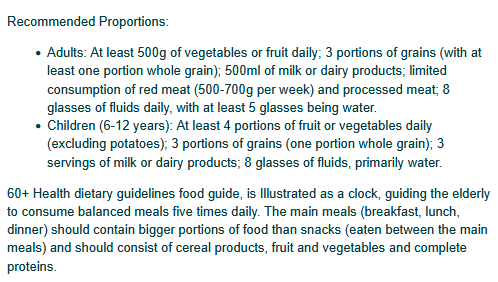

The Hungarian guidelines aren’t great:

No meat for children? I eat more red meat in a day than that (if i have red meat at my first and second meals) . I also eat nowhere near 1 pound of vegetables or fruits daily. Yikes.

IMHO, it is clear that the sat fat limit is kept there for political reasons. It makes no scientific sense, it makes no mathematical sense in the context of the rest of the document. Doesn’t surprise me, but it does disappoint me.

The guideline I looked at (“smart plate”, we have this since several years) has meats and weekly fish for children. It’s very similar for everyone, big emphasis on animal protein.

500g vegs is super little to me, I only could afford like 1000g on my keto (depended on the kind, of course, usually less) and it was just below what I felt the bare minimum so it got tough sometimes (raw vegan dishes helped a bit. 1kg fried veg was barely anything and very little in volume). I loved vegs. And I still love fruits. I just have learned to eat them in moderation.

It disappoints me too, because I see garbage being stated about the saturated fat guideline. Saw someone using an FFQ epidemiological study (one of those studies from Harvard) to show that saturated fat was “bad”, and ignoring the massive, expensive RCT from the US on 49,000 women for 8 years, which showed no benefit to saturated fat restriction.

It’s insane.

So more progress made than ever, and still complaining. Sounds like Teicholz. They’re not going to remove that cap, they can’t. Normal people aren’t eating low carb, they can’t start slamming the amount of fat low-carb eaters do, every low-carb person knows that. Just like when USDA removed Cholesterol as a “nutrient of concern”, it was the same crying point, that there was an upper limit. They’re never going to give advise to the 1% when the 99% is going to react a different way to it.

This IS progress. It will take time to re-educate. The mainstream has absolutely re-accepted eggs, avacados, real butter etc. Look how long that took!

It’s not insane. It’s corrupt. I used to be a cock-up theorist. I am now a confirmed conspiracy theorist.

Disturbing news about the saturated fats 10% major flaw in the beautifully described ‘captured [cafeteria] populations’. By Cripes, you can taste the political ducking and weaving in this US food guideline. The wide receivers (93% of the US population) are caught in a surprising swerve, a narrative reversal, a pivotal moment in the game, and are trundling down the sideline carrying the precious egg toward the end zone. But there is no game winning touchdown yet. Here come the vegan defence… stay tuned.

“But there’s another audience: the roughly 30 million children eating school lunches daily, plus military personnel, and the vulnerable populations—elderly and poor Americans—who receive food through federal programs, roughly 1 in 4 Americans each week. These programs are required by law to follow the Dietary Guidelines. For them, the numerical cap will trump any contrary language about butter and tallow. Cafeteria managers and program administrators will continue to adhere to the 10% limit, because that’s what the law requires.”

He’s too polarizing. I believe the majority of people are going to throw this improved nutritional advice out the window simply because it came out of his mouth, science be damned.

I think it’s not him so much as the times we’re living in. Some people on both sides automatically dismiss anything that anyone on the other side says. Which means no matter what, someone is going to criticize him.

I respect him. The old test of watch what he does versus what he says leads me there. He’s 71 year old guy, two weeks older than me, with ripped abs and does infinitely more pull-ups than I can.

Thanks!

Oh it has many things I agree with but that’s the case with our guidelines too. Of course they must do something right but the sodium and protein is more generous here than what I see elsewhere.

Our guidelines explains “portion”, I haven’t any idea about what a portion of grains or dairy is, after all, my dictionary has no such term. It should be individual how much we should eat from something and of course, we can choose. Our guide wants us to eat 500ml milk or similar amount dairy, whatever that means (I can’t convert milk into half-hard cheese or low-fat quark… they are just too different). Of course zero dairy is perfectly fine if one gets their nutrients elsewhere just fine. I would probably have great macro problems with 500ml milk and it’s almost no time to consume. Definitely not great for many people.

The recommended amount of full-fat dairy must contain a lot of saturated fat so the contradiction remains. Unless a portion means very little in the US but why would it.

It’s always weird to see “beans, peas, lentil, legumes” when they are all legumes. If people have no idea about it, why is it not something like “legumes (beans, peas, lentils…etc.)”?

I was surprised about the added sugar limit in crackers as I would think a cracker should contain zero to begin (but of course they use a little for flavor. even we have sausages with “<0.5% sugar”. not added, total though, most of it must be the paprika) with but I googled. A thing called “salted cracker” in a hypermarket here has more sugar than salt and it’s Hungary, not the US where even bread is sweet and meat dishes often are like that too.

Store-bought snacks tend to be quite horrible, there are good reasons I dropped them ages ago.

I agree. If he thinks that acetaminophen CAUSES autism, then there’s not a lot I can believe from him. And obviously, I believe that the current food pyramid/plate/whatever is completely wrong and unsupported by evidence.